The new edition of the Asia-Pacific Journal contains an overview of the recent books about the influential rightwing group, Nippon Kaigi, which Green Shinto has written about previously because of its close involvement with official circles in Jinja Honcho (Association of Shrines). (For more about Nippon Kaigi’s aims, see here.)

The piece is titled:

Dissecting the Wave of Books on Nippon Kaigi, the Rightwing Mass Movement that Threatens Japan’s Future

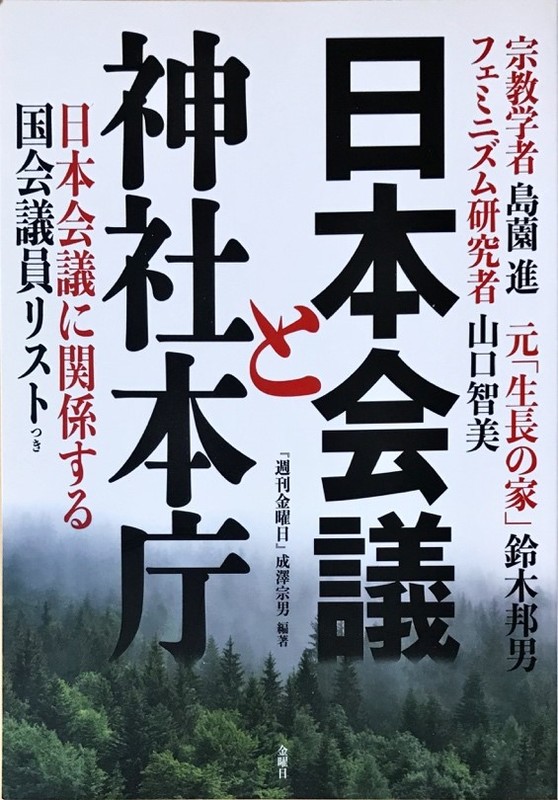

In this respect one book is of particular interest, Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honcho.

Nogawa Motokazu comments: ‘Most of the books provide a common understanding of Nippon Kaigi’s historical origins. It is symbolic that the title of the series written for Asahi shimbun, which became the basis for Fujiu Akira’s Dokyumento Nippon Kaigi [Document Nippon Kaigi] (Chikuma shobō 2017), the latest among all the books in the boom, was “Nippon Kaigi o Tadotte” [Tracing the Path of Nippon Kaigi] (November 6-21, 2016).

Authors don’t generally disagree about Nippon Kaigi’s historical background; I think they share a common understanding. For instance, they all say that a major moment in the establishment of Nippon Kaigi was the reign-name legalization movement. Although, in Nippon Kaigi no Kenkyū [A Study of Nippon Kaigi] (Fusōsha 2016),Mr. Sugano says “the movement for legislating the reign-name system was the beginning of everything”, he also says “the origin of Nippon Kaigi lay in its failure to pass the ‘Bill for the establishment of state support of Yasukuni Shrine’ [Yasukuni Jinja Kokka Goji Hōan].

I think what divides authors are their views on the source and extent of Nippon Kaigi’s influence and its source of funding. The Sugano book says that the Association of Shinto Shrines, which is often seen as Nippon Kaigi’s funder, is not so important. In chapter 5, titled “A Crowd of People” (Ichigun no Hitobito), he emphasizes the administrative skills of Nihon Seinen Kyōgikai (Nisseikyō) [Japan Youth Council], a group organized by former members of the right wing student movements, many of whom are former members of Seichō-no-Ie.

On the other hand, Yamazaki Masahiro in his Nippon Kaigi: Senzen Kaiki eno Jōnen [Nippon Kaigi: Passions to Return to Prewar Japan] (Shūeisha 2016) regards the Association of Shinto Shrines as crucial. Aoki Osamu’s Nippon Kaigi no Shōtai [Nippon Kaigi’s True Colors] (Heibonsha 2016) appears to be somewhere in between. Although Nippon Kaigi to Jinja Honchō [Nippon Kaigi and Association of Shinto Shrines] edited by Narusawa Muneo has “the Association of Shinto Shrines” in its title, Narusawa’s own chapter is titled “Nippon Kaigi to Shūkyō Uyoku” [Nippon Kaigi and the Religious Rightwing], which looks not only at the association but also at other conservative religious groups.

I think that we should neither overestimate nor underestimate the Association of Shinto Shrines. Certainly it sounds like a giant organization when we hear that there are 80,000 shrines in Japan. But in reality there are only about 20,000 so-called shinto priests. In other words, most of the shrines do not have full-time priests. Therefore, it clearly is an exaggeration to say that 80,000 shrines are mobilized in the movement. On the other hand, wealthy shrines hold significant power when we include their accumulated assets, despite their limited numbers. These issues need more research.’

Leave a Reply