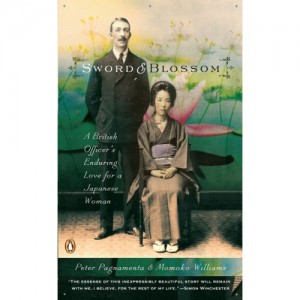

Sword and Blossom: A British Officer’s Enduring Love for a Japanese Woman by Peter Pagnamenta and Momoko Williams Penguin, 2006 345 pages

This is not a Shinto book at all, but a love affair between an Anglo-Irish officer, heir to a large estate, and an ordinary Japanese woman who bore him two children. Arthur Hart-Synnot was from a military family who saw service in the Far East as a career opportunity. Masa Suzuki was taken on as housekeeper and interlocutor.

The relationship is pieced together by the authors from a treasure trove of 800 letters, written by Hart-Synnot in Japanese on handmade paper in lengths of several feet which were carefully folded and enclosed with pressed leaves and dried flowers. They cover the period from 1904 to World War Two, but were only discovered amongst heirlooms in 1982.

It’s a fascinating read, not just for the relationship itself but for the wealth of detail in the background and times. In terms of international politics, it covers the period of the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of 1902, which emboldened the Japanese to take on the Russians in a campaign for which Hart-Synnot acted as observer.

The atmosphere of Meiji Japan and Edwardian England are graphically illustrated, and we learn of the love affair between Britain and Japan in these years when Japonism was all the fashion. The island mentality of the two countries was seen as cultivating people of similar stock, and a Japanese artist painted Britannia arm-in-arm with Yamatohime, founder of Ise.

With training from the British, the Japanese victory at Tsushima against the Russians was hailed as the greatest naval victory since Trafalgar, and fittingly it took place in the centenary year of the battle. Togo was seen as the reincarnation of Nelson, and bushido was celebrated as on a par with gentlemanship. ‘The English gentleman is a peaceful samurai, and the Japanese samurai is an armed gentleman,’ ran a World War One pamphlet. (How things had changed by World War Two!)

One of the hits of the era was a play called Darling of the Gods, which the Japanese ambassador went to see. He objected that people were forever bowing in conversation, whereas in reality Japanese only bowed at the beginning and end of exchanges. He also noted that Shinto and Buddhism were treated as if they were one religion, whereas in fact they were separate – an indicator of how much the Meiji split had taken hold by the early twentieth century.

Hirohito (Emperor Showa) dressed in the robes of high priest during his coronation ceremony in 1928 (courtesy of US Library of Congress)

A notable feature of the observations is the strongly patriotic spirit in Meiji times. ‘By far the most remarkable feature in the Japanese army is the wonderful feeling of devotion to the emperor and their country that pervades all ranks and arms,’ notes Hart-Synnot. One of his fellow officers spoke of ‘a fanatical wish to die for their country.’

In 1928 Hirohito was enthroned as the new emperor in Kyoto in a ceremony described by one observer as ‘a sacred pantomine’. The most intriguing aspect of the ceremonies is the Daijosai, where the emperor communes with the spirit of Amaterasu (there’s a good description on the Wikipedia site here.) At one point the new emperor dons a Robe of Heavenly Feathers, clearly a legacy of shamanic rites when the ruler-priest assumed authority by his ability to communicate with the spirit world. The present emperor controversially underwent the same ceremony (in Tokyo rather than Kyoto), which for some served to confirm his role as descendant of the sun-goddess.

Historically the narrative moves smoothly through the Taisho democracy movements to the increasingly militaristic and repressive 1930s. All in all, this is a fascinating and meticulously researched account of Japan in the first part of the twentieth century. It’s revealing too of the surprisingly close Japan-UK friendship of those times, until separate interests forced the countries apart. Oh, and there’s also an absorbing romance! It grows from infatuation to intensity of passion, but later takes a most surprising twist. It may not be Shinto, but this is a book well worth reading, and belongs up there with Samurai William as one of the most readable of books with a historical theme.

Thank goodness that with all the doom in the publishing world good writing still survives!

Leave a Reply