Pine torches flare up and sparks fly at Todai-ji's Nigatsudo

Spectacular evenings at Todai-ji at the moment, with the nightly Omizutori festival (described below). It’s on until March 14 and definitely worth checking out. Given the number of times wooden buildings have burnt down in Japanese history, it’s amazing anyone came up with this idea but somehow it’s managed to last for something like a millennium.

What does it all have to do with Shinto? Well, you could say Todai-ji was the first bastion of syncretism and it’s interesting that the building where the sacred water is kept is festooned with a shimenawa. Even today Shinto-Buddhist belief is clearly alive at the temple… (feature on Todai-ji’s Hachiman connection coming up soon)…

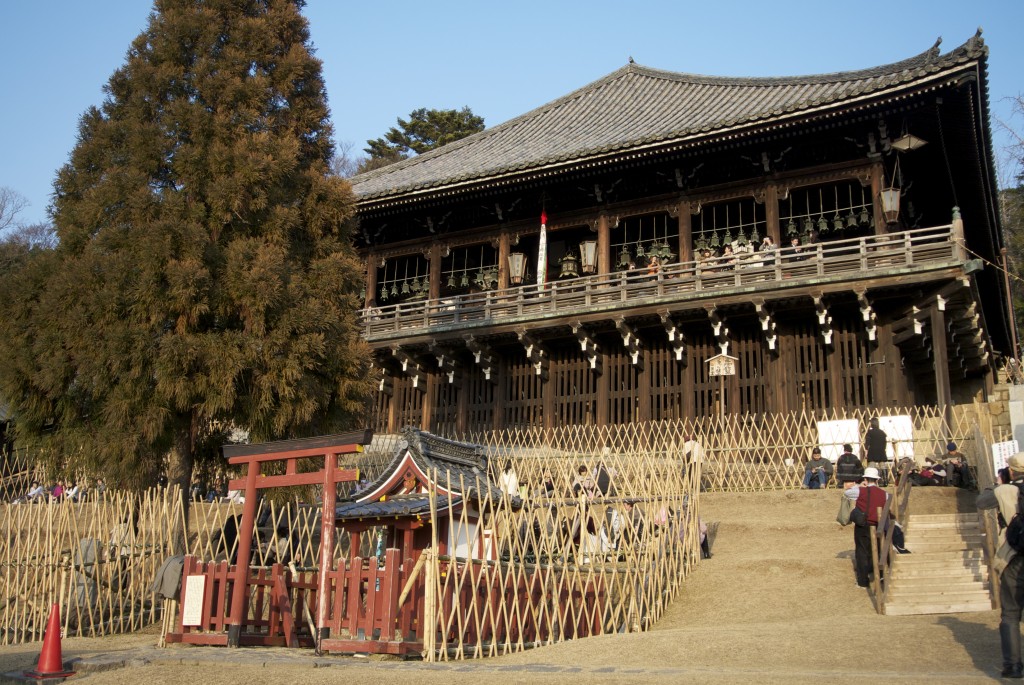

The Nigatsudo building where the festival takes place, in front of which is a small protective shrine

The building holding the sacred water

********************************************************************

The following courtesy of japan.com

Omizutori is the commonly used name for Shunie, a series of events held annually from March 1 to 14 at Todaiji Temple. This collection of Buddhist repentance rituals has been held every year for over 1250 years, making it one of the oldest reoccurring Buddhist events in Japan.

Omizutori is performed at Nigatsudo Hall, a sub complex of Todaiji, which stands not far from the temple’s main hall on the slope of a hill. Nigatsudo literally means “second month hall”, referring to the second month of the lunar calendar, when Omizutori has traditionally been held. The second month of the lunar calendar roughly corresponds to March of the solar calendar.

Fire at both end of the wooden building. A headache for the fire brigade, you would think...

Among the many different events held during Omizutori, Otaimatsu is the most famous and spectacular. Just after sunset on every night from March 1 through 14, giant torches, ranging in length from six to eight meters, are carried up to Nigatsudo’s balcony and held over the crowd. The burning embers, that shower down from the balcony, are thought to bestow the onlookers with a safe year.

The size of the torches and the duration of Otaimatsu vary from day to day. On most days, ten medium sized torches are brought up to and carried across the balcony one after the other, and the entire event lasts about twenty minutes, while the audience stands in the courtyard below the wooden temple hall.

On the 12th and 14th, however, the procedure is slightly different. On the 14th, the last day of Omizutori, the event lasts only about five minutes, but all ten torches are brought up to the balcony at the same time, making for a particularly spectacular sight.

On the 12th, the torches are larger and more numerous, and the ceremony lasts longer. It is also the most crowded day, so that most spectators cannot settle down in front of the Nigatsudo, but are kept continuously moving past the hall in a queue, limiting actual viewing time to around five to ten minutes.

In the night from March 12 to March 13 between around 1:30am and 2:30am, priests descend repeatedly from the Nigatsudo by torchlight to draw water from a well at the base of the temple hall. The well’s water is said to flow only once a year, and to have restorative powers. It is this event that is actually named Omizutori (“water drawing”). Yet the entire two-week event has become popularly known under its name.

Following the water drawing event, the mysterious Dattan ceremony is performed inside the Nigatsudo hall. During the ceremony, horns are blown, bells are rung and priests swing around burning torches inside the wooden building. The event comes to an end around 3:30am.

Dates: March 1st-14th (time and length depend on the day. Information available here.)

Lovely post! Was fascinated to read about these celebrations. They seem very similar to the Hindu festival of Holi which is just around the corner.

It is celebrated on the last full moon night of the month of Phalgun which is usually in February or March. Phalgun the last month in the Hindu Lunar Calendar and signifies the end of winter and the coming of Spring.

On the night of Holi, bon fires are lit on every street corner. Offerings of rice and other grains are poured into the flames giving thanks for the bountiful harvest. Crops are cut in mid January when the harvest festival is celebrated all over India.

The next day we ‘play’ Holi by throwing coloured powder and water on everyone. The colours welcome spring and the cooling water renews and refreshes as the temperatures begin to rise!

Thanks for that most helpful input. I’ve often wondered about the similarities of Shinto and Hinduism, for it seems there are many parallels. I was once doused in colours and water in Thailand, which presumably absorbed the Hindu custom via Buddhism…