On the eve of a major international conference devoted to Shinto and conservation, it’s pertinent to consider the implications of this breakthrough event and how vital it is to the future of Japan’s indigenous faith.

‘Greenwashing‘ is when a company or organisation seeks to gain advantage by falsely claiming that it is committed to green policies. It’s become so fashionable that every big environment-destroying multinational has jumped on the bandwagon. Even McDonald’s does it. But recycling paper plates while levelling huge areas of forest to feed corpulent carnivores is hardly likely to save the planet.

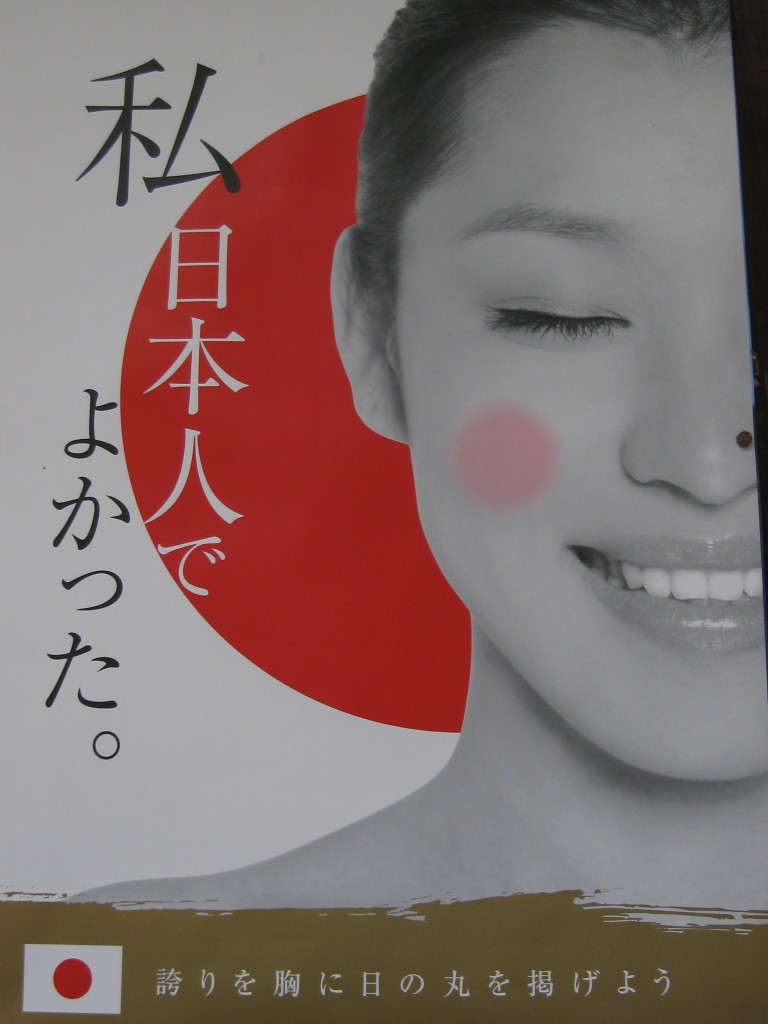

'It's good I'm Japanese' says a Jinja Honcho poster identifying with the risiing sun, symbol both of Japan and Amaterasu, the imperial ancestor

Jinja Honcho’s partnership with the prestigious international ARC (Alliance of Religions and Conservation) brings Shinto much kudos, for it becomes one of only 11 religions to hold such status. Even though it is all but restricted to one country, it becomes elevated thereby to global status. Yet though it benefits from the partnership, its record on green affairs raises serious questions.

In their book A New History of Shinto, leading scholars Mark Teeuwen and John Breen point out that while there is much in Jinja Honcho English-language literature about being a nature religion, this is downplayed in its Japanese-language literature. Moreover, its actions often point to other priorities, giving rise to a concern about greenwashing.

It may seem strange to question the commitment of an organisation representing an animist religion, but Shinto isn’t simply animist. It’s a religion of ancestor worship too. At a national level, this is expressed through worship of imperial ancestors, which means that it can become fiercely patriotic and centered around loyalty to the emperor. Expert observers like Lafcadio Hearn and Ponsonby Fane noted this long before WW2. Others, like Ian Reader, describe Shinto as a ‘religion of Japaneseness’ for this very reason.

The marriage of animism and ancestor worship finds supreme outlet at Japan’s premier Shinto shrine, Ise Jingu. Does it derive its primacy from being the seat of the Sun Goddess, Amaterasu ōmikam? Or does it derive its primacy from being the seat of the ancestral founder of the imperial line?

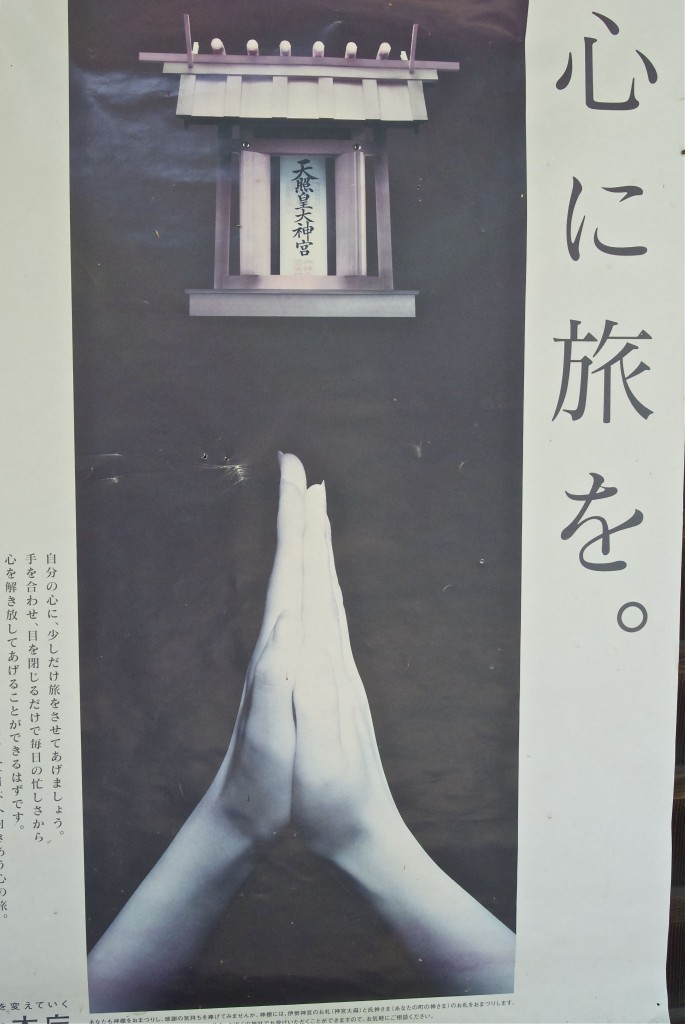

A Jinja Honcho poster showing hands in prayer to a talisman of Amaterasu, the Sun Goddess. Can we expect to see expensive campaigns in future promoting conservation issues?

The short answer is both, for ancestral and animist spirits have been conflated since ancient times. However, ever since the Meiji Restoration in 1868 an ideology has been in place to privilege the emperor and his lineage. That policy continues today in Jinja Honcho’s emperor-centred policy of promoting and funding the imperial shrine through a campaign of selling Ise taima (tailsman). This aims to raise awareness and money for the seat of the imperial ancestor. (At least half of the shrine’s income is said to derive from the sale of taima.)

While it is common to see Jinja Honcho posters promoting patriotism and the importance of Ise, I have never seen a single poster promoting conservation and commitment to green values. In addition, the semi-official publication Jinja Shinpō constantly carries pro-imperial articles and arguments in favour of defending Japanese interests, while at the same time belittling green issues and urging priests to be anti-animal rights (see page 6 of the contents listed here).

Can an organisation be anti-animal rights yet pro-conservation? In a paper for the Club of Rome, Martin Palmer of ARC has written: “The growth in concern about animal welfare is a recognition that other creatures have consciousness and is part of a return to an ethos that we are part of nature not apart from nature.”

Shinto thus stands at a crossroads. Is it part of a universal ethos based on being a part of nature? Or is it a particularist religion based on being apart from others? Is it going to devote its main efforts to boosting the imperial seat at Ise, or is it going to throw its resources behind the cause of conservation?

Near where I live in Kyoto, an attractive shrine along the grounds of Gosho (Former Imperial Palace) has engaged in a major piece of environmental destruction by cutting down trees immediately in front of its torii and clearing the ground to build a large, expensive apartment block (see photos below). This has no doubt been done to ensure the financial security of the shrine in a secular age.

'Let's pray at Ise' says this Jinja Honcho sponsored slogan, part of a concerted campaign to direct shrine visitors thoughout Japan to focus on the seat of the imperial ancestor.

But if Jinja Honcho was seriously concerned with conservation, surely it would be helping shrines like Nashinoki Jinja protect rather than destroy their green surrounds. Unfortunately this appears not to rank on Jinja Honcho’s list of priorities, however, because the whole set-up is directed towards taking money from small local shrines and funnelling it towards promoting the imperial cause. Small shrines suffer at the expense of the Ise taima campaign.

Why has there been no Shinto voicing of support for conservation and green issues? Why has Jinja Honcho not been a leading spokesman against the wide-scale destruction of the environment carried out by successive Japanese governments?

According to the horrific portrait of environmental damage in Alex Kerr’s Dogs and Demons, Japan uses more than four times as much concrete as the whole of the US – yes, the whole of the US (Japan is less than the size of California)!! All but one of the major rivers have been dammed, 60% of the coastline covered in blocks, and huge public works (not always necessary) litter the countryside.

One reason why Jinja Honcho has not spoken out is because of its close alliance to the political party responsible for all this: the LDP (Liberal Democratic Party). The right-wing, construction-friendly orientation of the party means placing profit before conservation, and political interests above the interests of nature. Because of its nationalist orientation, official Shinto has thus largely ignored conservation concerns.

The woods at Shimogamo Jinja in Kyoto offer a shining example of the work that Shinto shrines can do with their sacred groves

An example of the bias is given in A New History of Shinto (page 209), in which it is revealed that the first ever editorial in Jinja Shinpo concerning the environment only appeared in 2008 (why so late?). The editorial focussed on a need to protect shrine groves, not for ecological reasons but because they were able to foster in children a love of community and thus a patriotic love of Japan. Moreover, the woods were declared to be a means of restoring a sense of pure Japanese ethics and undoing 60 years of malign Western influence. What would ARC think of that?

One sees then that the collaboration between Jinja Honcho and ARC has enormous consequences, which could in time lead to a serious reevaluation of values. That is what makes this conference so exciting. Will the Association of Shrines continue looking to the past, reaffirming the structures of the Meiji Restoration and struggling with the legacy of WW2? Or will it look forward into the twenty-first century by committing itself to a genuine policy of conservation based on universal and animist values?

This blog has noted on several previous occasions that there are significant signs of green awareness by shrines and shrine priests. The Shasou Gakkai is a prime example, documented in a list of five green developments by Aike Rots here. In addition, in a most welcome recent development Jinja Honcho made a pledge to purchase timber for its shrines only from sustainably managed forests.

Shimogamo Shrine next to where I live has a shining example of conservation in its Tadasu no mori primal woodland. Moreover, Kifune Shrine just north of Kyoto says this in its shrine literature: ‘It is a shame that Japanese people seem to have lost their appreciation and respect for nature. Isn’t it time for the people of Japan to reclaim this special ‘Japanese spirit’ that was previously exhibited long ago? It is the hope of Kifune Shrine people all over the world will become aware of this ‘Japanese spirit’ and once again become involved in protecting our precious environment.’ (interesting attempt to combine particularism with universalism there!)

The time is thus ripe for a new Restoration. A Restoration of genuine animism, in which the Earth is treated as sacred and not as a commodity. Green Shinto has no doubt about where it stands. How about Jinja Honcho? This is what I hope to investigate over the coming two days.

Nashinoki Jinja in Kyoto is dedicated to heroes of the Sonno Joi movement (Respect the Emperor, Expel the Barbarians). It looks like a perfect match of ancestral spirits with animism...

... but it's sold off the wooded area directly in front of the torii, which has been cleared and concreted over to construct an exclusive apartment block. Can Shinto change to be a religion of conservation?

A religion of conservation, or (notice the flag) a religion of Japaneseness?

A very thought-provoking article John. Having recently visited Kifune Jinja, and read the english language material provided, I was struck by the section on ‘Planting Trees’ and the comment that Japanese people seem to have lost their appreciation and respect for nature. As you say, the current conference could be a real turning point for Shinto and conservation.

Hi John, this is a good and balanced overview article. You are right to point out the ambivalence in contemporary Shinto attitudes to environmental issues. I also agree that the current conference at Ise is potentially significant, not only for Jinja Honcho’s commitment to environmental issues but also for its relation to other religions, and the perception of Shinto abroad.

You write that Shinto “stands at a crossroads. Is it part of a universal ethos based on being a part of nature? Or is it a particularist religion based on being apart from others? Is it going to devote its main efforts to boosting the imperial seat at Ise, or is it going to throw its resources behind the cause of conservation?” Frankly, I don’t think it is a question of either/or. Yes, Shinto’s globalisation is likely to continue, with various non-Japanese devotees appropriating the tradition, interpreting it as nature worship no longer necessarily connected to Japanese territory. And yes, some people within Jinja Honcho and local shrines will probably continue to embrace elements of environmentalism. However, to Jinja Honcho as a whole these issues remain of secondary importance, their main concerns being the continuity of the imperial institution, Ise Jingu and its shikinen sengu, and state patronage of Yasukuni. I don’t think that will change any time soon.

To them, the conservation of shrine forests is perfectly compatible with the revitalisation of traditional culture and patriotic morality, so nobody within Jinja Honcho is against this type of conservation initiatives. That does not mean, however, that they are concerned with other environmental issues. Whaling is seen by them (either correctly or not) as an integral part of Japanese ‘traditional culture’, and one of the few areas where Japan proudly resists outside pressure. That, to conservative Shintoists, is much more important than ‘animal rights’, which they reject as something imposed by ‘the West’. Just because they appropriate certain aspects of environmentalist discourse does not mean they accept the whole package…

But then, Jinja Honcho does not represent Shinto as a whole, and there is quite a lot of diversity within the tradition. Generally speaking, I think Shinto attitudes to environmental issues have changed quite a bit in the course of the past twenty years or so.

Thank you for those thoughts, Aike. What you say is persuasive, and I very much agree with the points you make. What will be interesting is how far engagement with ARC and the Western conservation ethos will affect thinking within the Shinto establishment. At the very least it should prompt greater diversity.

Interesting article. Just a note about Nashinoki Jinja.

Jinja Honcho consistently refused the shrine permission to cut those trees down, partly to preserve the trees, and partly because the building will go right across the sando. In the end, Nashinoki (which was a beppyo jinja, under the direct supervision of the central Jinja Honcho) left the association so that it could go on with the project.

The motivation was to get enough money to keep the shrine viable, and I entirely agree with you that Jinja Honcho should have been offering help, rather than just forbidding the rebuilding. Indeed, I wrote a piece about it on my Japanese blog at the time. However, as a beppyo jinja, Nashinoki does not really qualify as a small shrine.

(The final step, when Nashinoki left Jinja Honcho, was covered in some detail in Jinja Shinpo, which is my source for this.)

Many thanks for that background information, David. I heard personally that part of the problem was that the apartment would be overlooking the Former Imperial Palace, though of course the

main point at issue is the financial situation of the shrine. One wonders how many other shrines are close to bankruptcy and in need of selling off their surrounds…