You’re regarded as the high priest of Shinto and chief ritualist of the realm. Your grandfather was considered a living god. Your family line claims descent from the Sun Goddess and has ruled as emperor for 126 generations. With a pedigree like that, what kind of a memoir could you possibly write?

You’re regarded as the high priest of Shinto and chief ritualist of the realm. Your grandfather was considered a living god. Your family line claims descent from the Sun Goddess and has ruled as emperor for 126 generations. With a pedigree like that, what kind of a memoir could you possibly write?

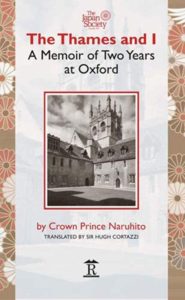

The book in question was first produced in 2006 by the then Crown Prince Naruhito, now Emperor of Japan. This year it has been reissued as a paperback to coincide with his inauguration. It’s entitled, ‘The Thames and I: A Memoir of Two Years at Oxford‘ (Renaissance Books, 2019).

As the subtitle suggests, it’s an account of the Crown Prince’s time as a student at Merton College, where he spent two years studying 18th century navigation on the River Thames. It’s also a part-guide to Oxford, to the way the university works, and to the history of his college. There are cultural observations too on the English and the way the island country resembles but differs from Japan. In so doing, Naruhito gives one of the best overviews of English classical music I’ve seen (a special interest of his, since he plays the viola to a high standard).

Dreaming spires – Naruhito was in Merton College, with claims to being the university’s oldest

By far the most intriguing part of the book, however, are not the factual passages but those that offer insight into the crown prince’s lifestyle. We learn for instance that he is accompanied by two police guards, who take it in turn to watch over him and who act as cultural informant and language aide. They even play a part in helping with his research. As we know from Princess Di and films on the subject, bodyguards and the people they protect can strike up close friendships.

There are some amusing touches, and he confesses to several ‘blunders’ such as spilling coins across the floor.. He had never used a washing machine before and overfilled it with washing powder, so that soap suds flooded across the floor. But by the end of his stay he had mastered how to iron his own clothes. As you might expect, the writing is discrete and circumspect. At one point he meets a challenge to drink five cups of an alcoholic concoction, but he writes not a word about how he feels afterwards. In fact, there’s not a single person who could be offended by what he writes. He makes friends wherever he goes.

In many ways it’s an enchanted time, as if he’s escaped from the starightjacket of Kunaicho (Imperial Household) like the male equivalent of Audrey Hepburn in Roman Holiday. The people he meets are all kind and entertaining. He very much enjoys the conversations he has, with people in all stations of life. His tutors at Oxford are inordinately wise and helpful. When he goes abroad, he’s invited to stay in castles and palaces by European aristocracy. He enjoys his meetings with the royal family. He climbs the tallest mountains in Scotland, England and Wales. He travels extensively. And he even has time for study as he chases up ancient documents in obscure archives. As he explores the world of eighteenth century transport on The Thames, he learns to love the river that flows close by his college.

Through all this, Emperor Naruhito comes over as humble, modest, well-read and likeable. He’s very much an international figure and a man of his time, a modern monarch one might say. One can’t help feeling that he’s certainly not someone the ultra-right in Japan would choose to champion as their semi-divine national symbol. This struck me this week while watching the new emperor and Masako welcome with ease Trump and his wife to the imperial palace. It was Naruhito who was making the small talk. In English. Far from being overshadowed by the greater stature of his guest, he looked pleased at being able to entertain the most powerful man on earth.

But what of Shinto you might ask? I read the book with great interest, not only as a former citizen and author of guidebooks to Oxford, but as someone who thought there may be a mention or two to shed light on his attitude to his native religion. But there was not a word, not a suggestion even. There were passages about European cathedrals, but nothing about Ise or Izumo. There were observations on nature, the ascent of mountains, a lot about the River Thames, but nothing that indicated the vital role of such phenomena in the religious life of his native country. Not even an animistic hint. I found this odd, though perhaps it was because his focus was fixed so steadily on England. But surely someone brought up to be a symbol of his country must be imbued with awareness of a tradition that is so indelibly woven into the national culture? I confess to a touch of disappointment.

Notwithstanding that, the book is a charming read for anyone with the least interest in how Japan will fare in the coming era under this engaging figure. Let’s hope he has the strength of character to go with his undoubted sensitivity. In these troubled times he may well need it.

**************

The Main Hall of Jingu Kaikan fills up with an international audience to hear the talk by Oxford-educated Princess Akiko on what Shinto means to her

For insight into how the imperial family might regard Shinto, a talk by Princess Akiko (daughter of Prince Tomohito of Mikasa) at an Ise conference shed light on subject. You can read the whole report here, but let me quote an extract from my report of her speech….

The talk by Princess Akiko raised the question of whether Shinto was a matter of belief or simply part of the Japanese way of life. With a doctorate in Japanese art history from Oxford University, she spoke of her impressions of living abroad. Japan was said to be proud of having four seasons, she noted, but Britain often had four seasons in one day. Moreover, whereas British water was good for black tea, Japanese water was good for green tea.

But what made the most impression on her was the British supermarkets had the same food throughout the year, which made her miss the seasonal nature of Japanese food. There was something in Japanese culture that was in tune with the changing seasons of nature. It had to do with an affinity for the deities living in rocks, waterfalls and trees, etc. It was, she suggested, difficult for foreigners to appreciate.

It was the pluralism of Japanese thinking that led to another aspect difficult for foreigners to comprehend. ‘Born Shinto, marry Christian, die Buddhist’ was an accepted path in Japan. Because of polytheism, it was easy for Japanese to accept any kind of deity as valid. She herself had felt power and refreshment from a rock at Suwa Shrine named after Susanoo no mikoto. And as a child, she had felt a sense of awe at the woods of Ise Jingu.

So what in the end was Shinto? ‘Pay respects and have gratitude to the kami,’ she had been told by a priest. It’s not a question of salvation or belief as in Abrahamic religions, but of simple things like saying itadakimasu before meals and gochisosama afterwards. For Japanese these aspects of daily life enrich their existence. There was little doubt this pertained to the imperial family too.

Leave a Reply