In 2020 I travelled by train from Japan’s most northerly station (Wakkanai) to the most southerly (Ibusuki). The three-month journey was inspired by a love of travel, and a desire to see parts of Japan I had yet to visit. And so one fine day in August I set off shortly after Obon to catch the late summer sunshine in Hokkaido. Like Donald Richie, I thought I could find the essence of Japan by travelling through the lesser known parts of the country, but whereas he explored The Inland Sea, my journey was largely along the Japan Sea, avoiding the ‘Golden Route’ of Tokyo – Kyoto – Osaka – Hiroshima.

On the way I wanted to stop at places of note and find what made them special. I was particularly keen to visit the jokamachi (castle towns), as these Edo-era strongholds remain regional hubs of arts and crafts. And so one fine day I flew to Sapporo and headed by train for Wakkanai. My first port of call was Cape Soya, Japan’s most northerly point with views of distant Sakhalin. My companion was a young Buddhist priest called Hirota san, a member of the Jodo Shinshu sect, who had asked to join me for the first week. It was from Soya that Alan Booth started the walk described in his celebrated book Roads to Sata (1995).

This series of posts may not always be specifically about Shinto, but I hope it will illustrate how its values are deeply embedded in the Japanese way of life. After thirty years of living in Japan, I have come to the conclusion that more than a nature religion, Shinto is a religion of Japaneseness.

*******************

Cape Soya

The chief attraction at Cape Soya – the whole point of it – is a monument marking Japan’s most northerly point, in front of which visitors pose for photos. Nearby is the statue of a samurai holding a yardstick. Mamiya Rinzo (1775-1844), a famous cartographer, had led an expedition to Sakhalin and confirmed for the first time that it was an island. Accompanying him were six Ainu, yet there was no mention of them – a bit like celebrating Hillary but omitting Tensing in the conquest of Everest.

A few miles from the Cape, Hirota san and I noticed a small rough looking memorial, erected by descendants of the six Ainu on Mamiya Rinzo’s expedition to Sakhalin. It showed the importance of ancestral ties, and the location away from the Soya spotlight spoke to the marginalisation of Ainu in Japanese history. Few in number, the ethnic group have a disproportionate significance, for they blow a hole in the nationalist construct of ‘one race, one nation, one language’. I was planning to learn more about them at the Ainu sites around Asahidake and the newly opened Ainu National Museum at Shiraoi. This was after all for millennia the land of kamuy rather than kami, and still today some 80% of place names in Hokkaido are Ainu.

*****************

Rishiri Island

Rebun and Rishiri are two attractive islands that can be visited by ferry from Wakkanai. Rishiri is dominated by the conical slopes of its mountain, one of Japan’s many mini-Fujis. On the bus tour round the island a monument caught my attention…

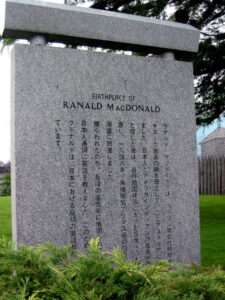

At one point the bus passed a simple rock monument close to the sea, of great interest to me personally but not so much to the others. It marked the spot where the splendidly named Ranald MacDonald arrived on a one-man mission in 1848. His was an extraordinary story. Son of a Scottish father and Chinook mother, he was raised in western Canada where he developed an obsession with the forbidden land on the far side of the Pacific. Japan was still in self-imposed isolation, and imprisonment or death awaited intruders. Nonetheless, bored of his job as a bank clerk, MacDonald signed on for a whaling ship and persuaded the captain to abandon him off Hokkaido. The crew must have thought him insane.

When he washed up on Rishiri, MacDonald pretended to have capsized and was taken captive, then despatched to Nagasaki where those in charge of foreign affairs were based. For some time American and British ships had been skirting Japanese waters, and the captive offered a chance to learn their language, so fourteen samurai who had previously learnt Dutch were appointed to study with him. MacDonald thus became Japan’s first ever English teacher. How did lessons proceed? What method did he use?

The lessons came to an abrupt end after ten months, when MacDonald joined a group of shipwreck survivors released to an American warship. In later years he tried his hand at business but died a poor man, his last word being, ‘Sayonara.’ History suggests he did a great job as teacher, for one of his students, Moriyama Einosuke, became a leading interpreter in the historic negotiations of 1854 with Commodore Perry.

Back in the bus the commentary continued at full speed. Mackerel were once so plentiful that in the poverty following WW2 people flocked to fish at Rishiri. Fishermen put up Shinto shrines in gratitude, which explains the large number. Scallops too were found in abundance. ‘Now, if you would please turn to the left, you can see the kelp hanging up to dry, while on the right is another famous face of Mt Rishiri. Please look left again and you can see the Hokkaido mainland.’ Heads were swivelling from side to side as at a tennis match.

Thank you for this most interesting post. It took me away from myself to Japan, a place I sorely miss. I loved the Alan Booth books that I read long ago. I hope the posts of your travels keep coming as I will look forward to them.

By the way, I wonder if you have heard of Reverend Baruch who is head of the Shinto Shrine in Granite Falls, Washinton near Seattle. As a former guide at the Seattle Japanese Garden, I have been most fortunate in meeting him as he blessed the garden on opening days each year and visiting the shrine that, just like ones in Japan, is located in a lovely bucolic setting.

Thank you for the feedback, and yes indeed I have visited the very attractive shrine near Seattle and actually interviewed Rev Barrish for Green Shinto…

Thank You for posting wonderful history pieces on Japan. I am very interested in the Japanese history. Coming from America where our history is very relatively short I have taken on learning as much as I can about Japanese history which is a daunting task as Japanese is a daunting language for me in my old age.

Thank you very much for bothering to write in. Much appreciated.