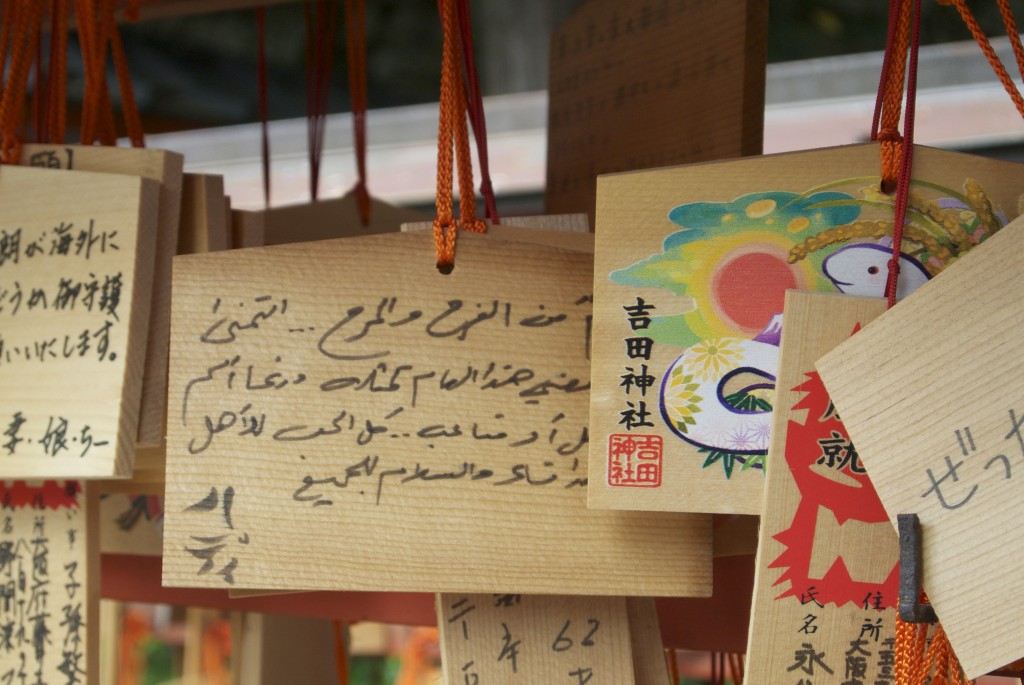

Torii tunnel at Fushimi Inari, one of the 57 shrines given detailed attention in 'Shinto Shrines'

I’m happy to be able to report that Shinto Shrines has been garnering good reviews, and I’m especially pleased for the main author Joseph Cali who put in an inordinate amount of effort into the book. Here are two of the reviews so far, the first being by one of the best writers on Japan now that Donald Richie has passed on. The other is from a reviewer for the British Chamber of Commerce, who seems to be (surprisingly) well-informed on the subject.

********************************************

A double dose of guidance offers more than usual information

A double dose of guidance offers more than usual information

BY STEPHEN MANSFIELD APR 28, 2013 Japan Times

SHINTO SHRINES: A Guide to the Sacred Sites of Japan’s Ancient Religion, by Joseph Cali with John Dougill. University of Hawaii Press, 2012, 328 pp., $24.99 (paperback)

Irrespective of whatever faith you might hold, or if you count yourself among the growing ranks of the agnostic, shrines can be appreciated as much as a cultural experience as a religious one. For native religions to flourish, an appropriate national character or mind-set has to exist.

Accordingly, the writers of this new and much needed guide, two well-established authors on Japanese culture, examine the fertile socio-psychological ground that made it possible for Shinto to secure a firm purchase in Japan.

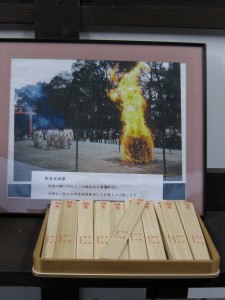

With no central book, the religion must be practiced and well supported to thrive. Shrines are generally very well maintained in this country. It is a rare case to come across a truly dilapidated one. It would be like abandoning the gods.

While the book covers well-known places of worship like the Meiji and Ise shrines, there are structures that may not be familiar to all readers, like the modest Aiki Jinja in Yoshioka, Tsubusumu Jinja, a shrine located on a small island in Lake Biwa, and Yukoku Inari Jinja in Kyushu, its main structure built on vermilion-colored scaffolding. The guide provides detailed background information on architecture, customs and rituals, clothing, symbolism and much more. It also gives the reader a rundown of all the major deities, a necessarily short list given that there are a whopping 8 million of them.

I’ve always thought of Shinto as a pantheistic belief, the mother faith in many ways of all people, the religion having its roots in the animism and shamanism that defined the practices of many ancient communities in the world.

And with no founders, prophets, miracles, or divine channeling of messages, Shinto may be one of the more credible of today’s faiths, it’s reverence for nature sitting well with the concerns of a green age. Predicated on the idea of coexisting with the forces of nature, rather than exploiting them, there is much to be learned from this non-doctrinal faith and this fine guide to all its intriguing aspects.

*****************************************

– British Chamber of Commerce in Japan: Acumen (Feb. 2013)

Shinto is the indigenous and older of Japan’s two main belief systems (the other being Buddhism, a 6th-century import). It rests on faith in kami (spirits) – although gods is the usual, though slightly misleading, translation – that are to be found in everything, from people and animals, to places and even inanimate objects such as rocks or trees. Thus. it is a faith that is at the same time polytheistic. pantheistic, animistic, and something that is surely special. Shinto rites and practices are very much alive in today’s Japan. so much so that most Japanese take them for granted and many would be surprised if reminded that they were practising Shintoism.

For the majority of non-Japanese. the most obvious encounter with Shinto is at the many shrines that are all around us (an estimated 80.000 nationwide). Cali and Dougill’s impressive book, presenting itself as a guide to just a select few of these, is far more than that. The introduction is easily the clearest and most accessible explanation of Shinto that I have read. There is an immense amount of detail about the history of Shinto, the types of kami, and how this most Japanese of faiths interrelates with Buddhism, Confucianism and Christianity, among other belief systems.

There are numerous helpful illustrations, including ones of the most important features of a typical shrine, as well as of the clothing worn by priests and shrine attendants. In addition, of great interest is the way that the authors pose the question: “What benefit might there be in visiting a shrine for someone who has grown up in another country with different cultural and religious values?” Their answers are compelling.

The authors’ enthusiasm is infectious and the depth of their knowledge, and obvious love and respect for the subject, is evident on every page. Thoroughly researched, well written and cleverly illustrated, the book should be a must-read for anyone wishing to delve into this most fascinating aspect of Japanese culture.

Kasuga Taisha, another of the 57 shrines described in detail in the book

A double dose of guidance offers more than usual information

A double dose of guidance offers more than usual information