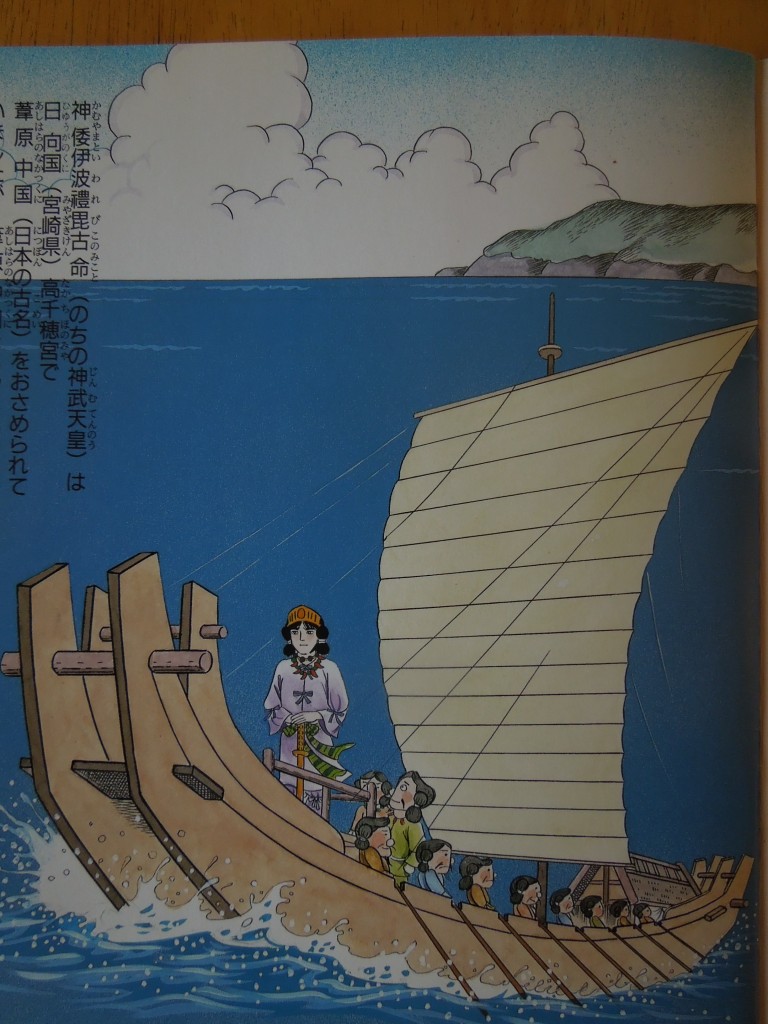

Emperor Jimmu, putative founder of the imperial line

Shinto mythology tells of how a descendant of the sun goddess named Jimmu, who was living on the east coast of Kyushu, set off to bring ‘enlightened rule’ to the troubled provinces in Honshu. Accordingly under the leadership of his elder brother (Itsuse no mikoto) Jimmu set off on a journey of conquest, passing along the Inland Sea by boat and landing abortively on the west coast of the Kii Peninsula, where his elder brother was killed and his forces pushed back by opposition from local clans.

The beach at Kumano where Jimmu is said to have landed his invasion force

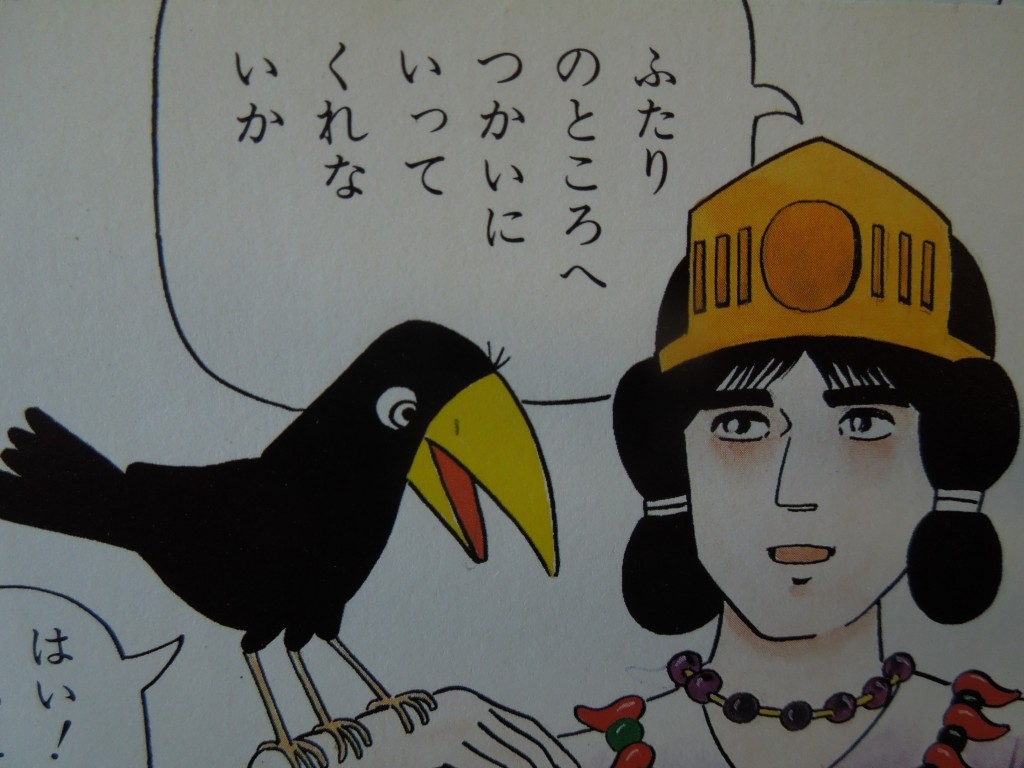

Realising as a descendant of Amaterasu he should attack with the sun at his back, Jimmu moved around to the east coast and landed on a Kumano beach south of Shingu where he made his way inland but was unable to progress further in the mountains. At this point Amaterasu sent a three-legged crow to guide him onwards.

After reaching Kashiwara in the Yamato river basin, he set up a palace and became the first emperor of a fledgling state that was later to conquer the rest of Japan. Accordingly he is no. 1 in the imperial line, of which the present emperor is no. 125. (For a full list, see here.)

Historians doubt that there was ever any such figure as Emperor Jimmu. On the other hand, as with King Arthur and other legends, it’s possible that the story holds a nucleus of truth and reflects a race memory of past migration. Jimmu might even be a composite figure, around whom stories of the past coalesced. In this respect it’s interesting to trace the local legends that have accrued around the path of conquest.

Takashima Island in the Inland Sea, where Itsuse and Jimmu are believed to have made camp

The story begins in Miyazaki, where the city’s eponymous shrine honours him as kami and claims to stand on the site of his palace. In the Inland Sea, off the Okayama coast, is an island where Itsuse and Jimmu are said to have made camp and rested before launching their attack on the west coast of the Kii Hanto, somewhere in the area around present-day Osaka. The remains of a prehistoric castle have been unearthed on the island.

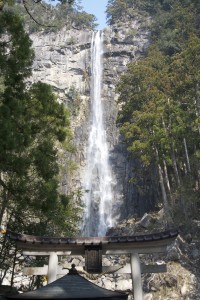

On the Kumano coast, south of Shingu, is a beach where Jimmu is said to have landed, and not far away is a memorial stone marking the place where he is believed to have built a small palace. Thereafter it is said that he noticed a strange light some twenty kilometers away, and when he went to investigate it turned out to be the mighty Nachi waterfall, the biggest in Japan. Realising the force of the kami, Jimmu made due acknowledgement to its spiritual presence, thereby initiating worship at the falls.

The sacred Nachi waterfall, allegedly discovered by Jimmu

Following this Jmmu made his way up the peninsula, and it’s reasonable to suppose he would have used the Kumano River as a means to progress inland, travelling upriver as far as Hongu or beyond. The river now has little water but in past centuries served as an important pilgrimage route with boats running between the coast (Shingu) and the main shrine of Hongu some forty kilometers away.

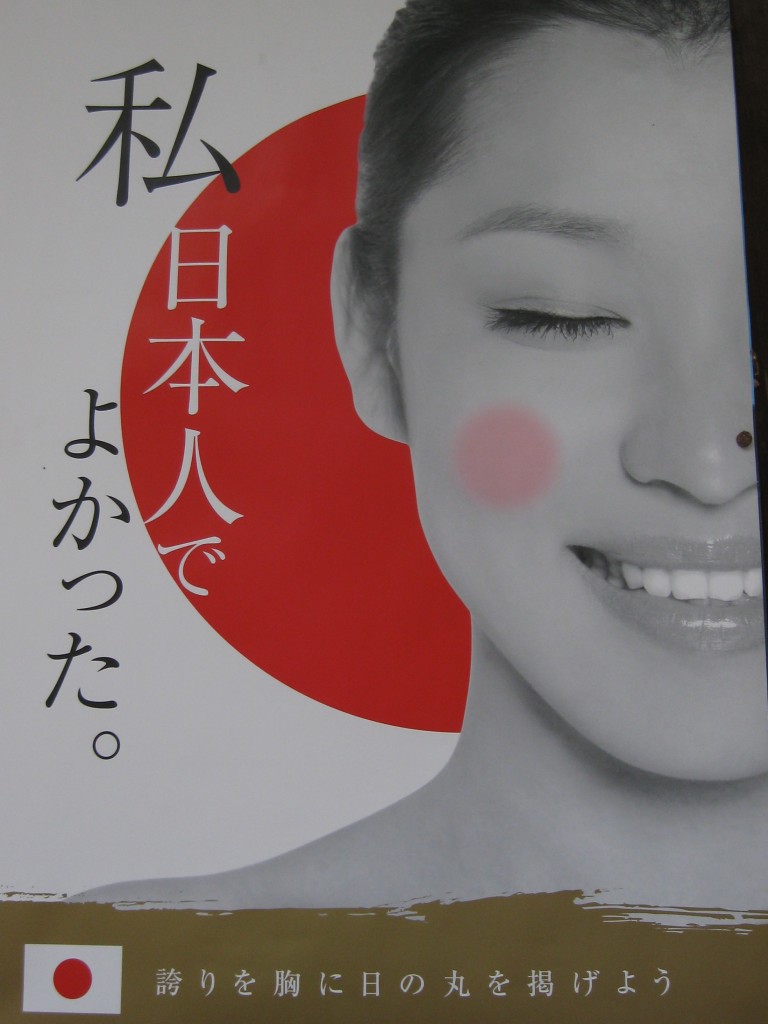

According to legend, when Jimmu reached the Yamato area, he built a palace where Kashihara Shrine now stands, and in Meiji times his supposed grave was located nearby using Kojiki mythology as a guide. He reached the peak of his fame in 1940 when he was made a hero of State Shinto and enormous celebrations held for the “2600th anniversary” of this putative founder of Japan. Now, like King Arthur, he’s a figure enveloped in myth and romance, subject to speculation by historians as to how much fact there really is in all the fantasy.

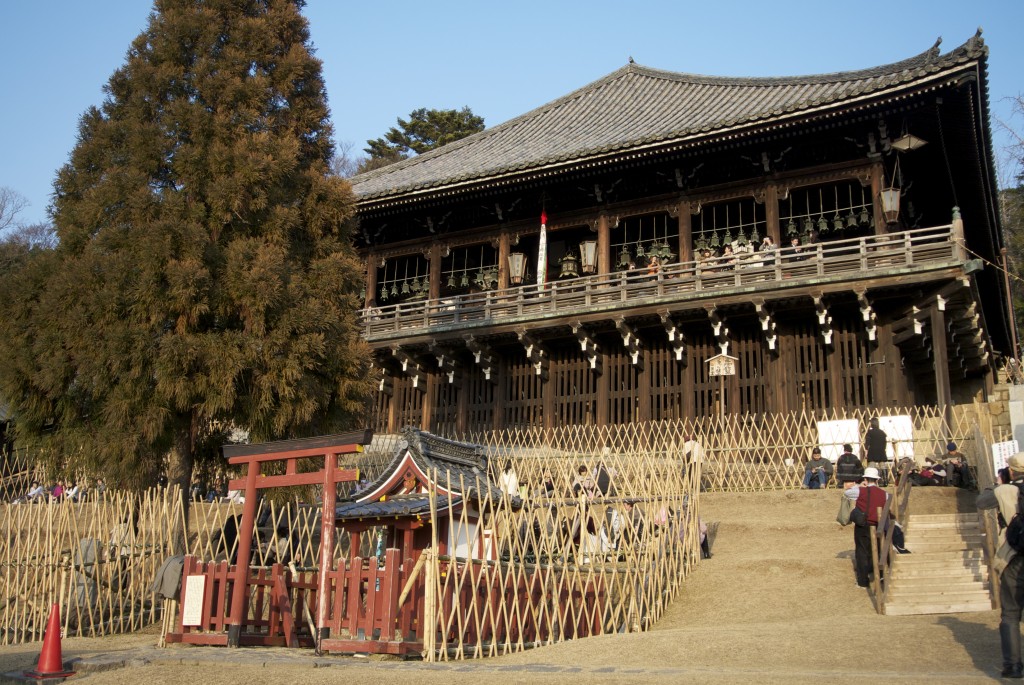

Kashihara Shrine, supposedly built on the site of Jimmu's last residence and near his final resting place.

Kashihara Shrine picture book story of Jimmu: here he sets out on his expedition

A three-legged crow guides Jimmu through the Kumano mountains

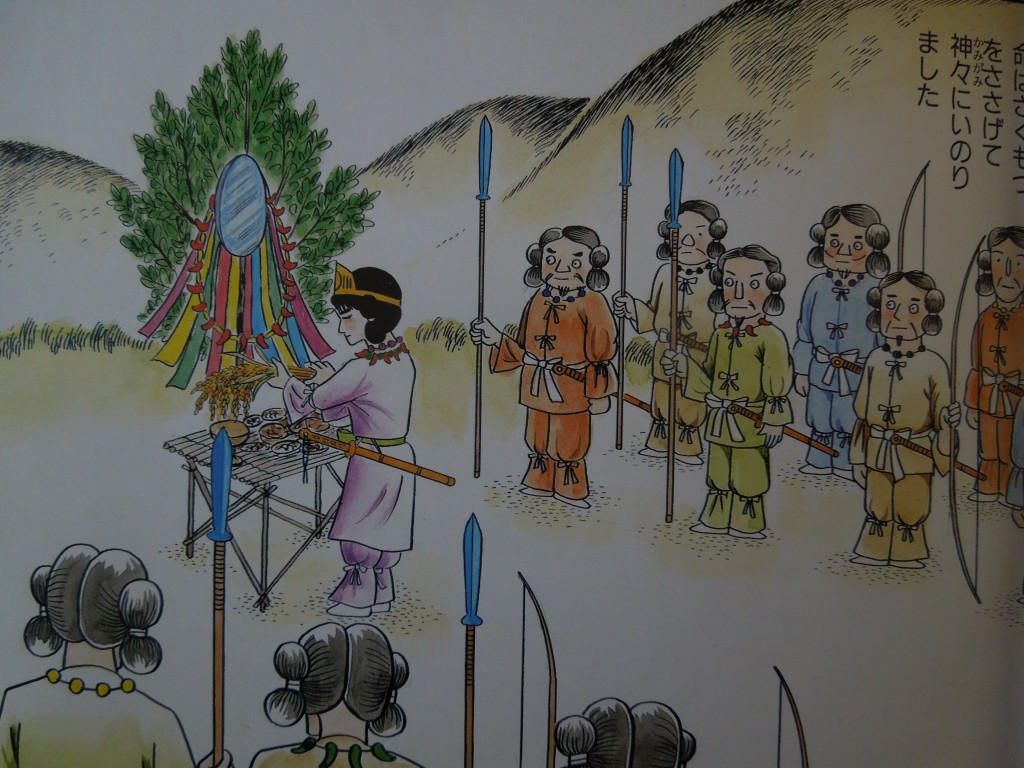

Jimmu holds a ritual of gratitude to his ancestor Amaterasu for his salvation

At Kashihara Jimmu holds court and initiates the business of state