Hawaii Kotohira Shrine

In 2005 I went on a trip to Hawaii and visited six different Shinto shrines there – Kotohira, Izumo Taisha, Ishizuchi and Daijingu in Honolulu, plus Hilo Shrine on Hawaii island and one on Maui. At the time information was hard to come by, and I thought that I had visited all of the Hawaii shrines, but checking on the internet just now I see Wikipedia has a listing of seven shrines in Hawaii, the extra one being Ma’alaea Ebisu Jinsha about which I know nothing.

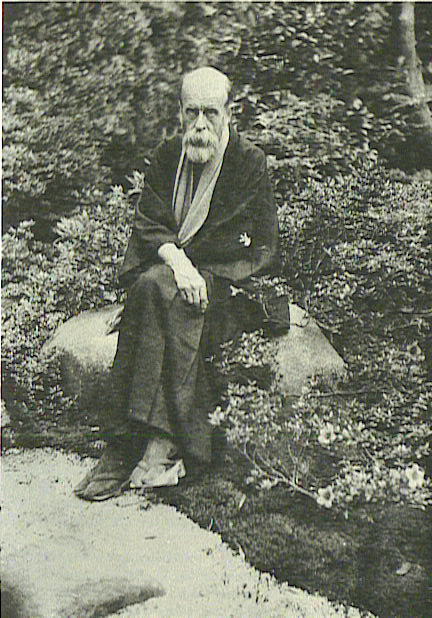

Rev Watanabe at the Hilo Shrine

My interest lay in how Shinto fares outside its home base of Japan, and to what extent it catered for non-Japanese. In this respect I had talks with Rev Okada of Izumo Taisha and Rev Watanabe of Hilo, and I also attended a morning ritual at Ishizuchi Jinja. I’d read reports of how in contrast to Buddhism, Shinto was prone to fade outside Japan as emigrants lose their culture and become assimilated. The religion originated after all in communality and ties to the land.

There were several surprises, such as the church-like pews at Hilo and the bilingual golf omamori (amulet) at Kotohira Shrine. But the biggest surprise was that George Washington had been enshrined as a kami. This seemed a huge leap in terms of Shinto, with enormous implications for how the religion could spread beyond Japan. Though I was eager to learn more, I couldn’t find out very much about it.

Later I got in touch with Paul Gabriel Gomes, an MA student working on a dissertation about Shinto in Hawaii, who told me that both George Washington and Kamehameha the First were enshrined in 1921 by Rev Kawasaki (according to an undergraduate paper done right before the war in June 1941).

Paul wrote to me as follows: “From my interview with Rev. Okada (at Izumo), it seems that Rev. Kawasaki was a very progressive thinker for his time and profession. There doesn’t seem to be much evidence that the central Ise authority tried to impose much guidelines on the shrines in Hawaii. Also it seems like something that non-exclusivist religions tend to do here. The Daoist shrine in Chinatown has a small area where “akua” (local Hawaiian gods) are kept.”

Apart from the kami at Hawaii Izumo, the other evidence of indigenisation was at Kotohira Shrine (full name, the Hawaii Kotohira Shrine-Hawaii Tenmangu Shrine). The priest there Rev Takizawa is apparently very active, though he was away in Japan when I called. It seemed the most flourishing of the shrines I visited, and I gathered that many non-Japanese participate in festivals and events such as the New Year celebrations.

The American orientation of the shrine was conspicuous, with Stars and Stripes on display, and to my amazement there was an amulet called ‘Spirit of America Omamori’, the sign for which said ‘Show your American spirit and resolve with our exclusive patriotic omamori.’ Shinto is often described as a religion of Japaneseness, so it was striking to see it being used to promote American patriotism. It could be said to provide a model of how Shinto can make the leap to a different culture, though Green Shinto would advocate a different path which is based on the spirit of universalism.

Maui Shrine

At Maui, there was a different picture of how Shinto had fared in Hawaii, for the impressive shrine buildings were in a bad state of repair. I gathered there was an elderly female priest, who was unable to function very well, and that it was more or less unused. I read later that the building was being considered for conservation (see here).

From his research Paul Gabriel Gomes was able to summarise for me the overall situation in Hawaii as follows:

“Shinto is relatively miniscule outside of Japan when compared to Japanese Buddhism, and many think it’s a declining religion of elderly here. I’m finding that it’s almost amazing that Shinto persisted after WWII considering both the governmental pressure and the grass-roots social pressure exerted on it.

Japanese Buddhism took up some of the functions of Shinto here in Hawaii, and there was heavy organized pressure from Christian missionaries. It seems Shinto was a small second partner to Buddhism here even before the war.

The Shinto groups that persisted here seems to be linked with a singular charismatic authority that held the community together. Shinto practice in Hawaii is much more reminiscent of practice in Japan than Japanese Buddhism in Hawaii is of Buddhism in Japan. Shinto is melded into the larger social fabric of Hawaii in ways which skirt the borders of secular and religious, esp. with Shichigosan and New Year’s.

Maui Jinja might already be non-operative and I know that Ishizuchi Jinja is down to a handful of members. However, while the priests I’ve interviewed say there is decline in general, the non-Japanese elements of the population visiting at New Year’s, requesting services and becoming members is up, though nowhere near the amount necessary to make up for deaths and secularization.”

*********************************************************************

For a report on Shinto in Hawaii from 1984 by a professor of religion, see here. For a symposium on Shinto and internationalisation, which includes a report on the Hawaiian situation, see David Chart’s blog here.

**********************************************************************

Ishizuchi Shrine – a touch of Greek about the pillars between the two sets of torii?

Hawaii Izumo Shrine – with chararacteristic Izumo architecture and thick shimenawa rope

Adaptation – Hilo Shrine with what looks very much like church pews