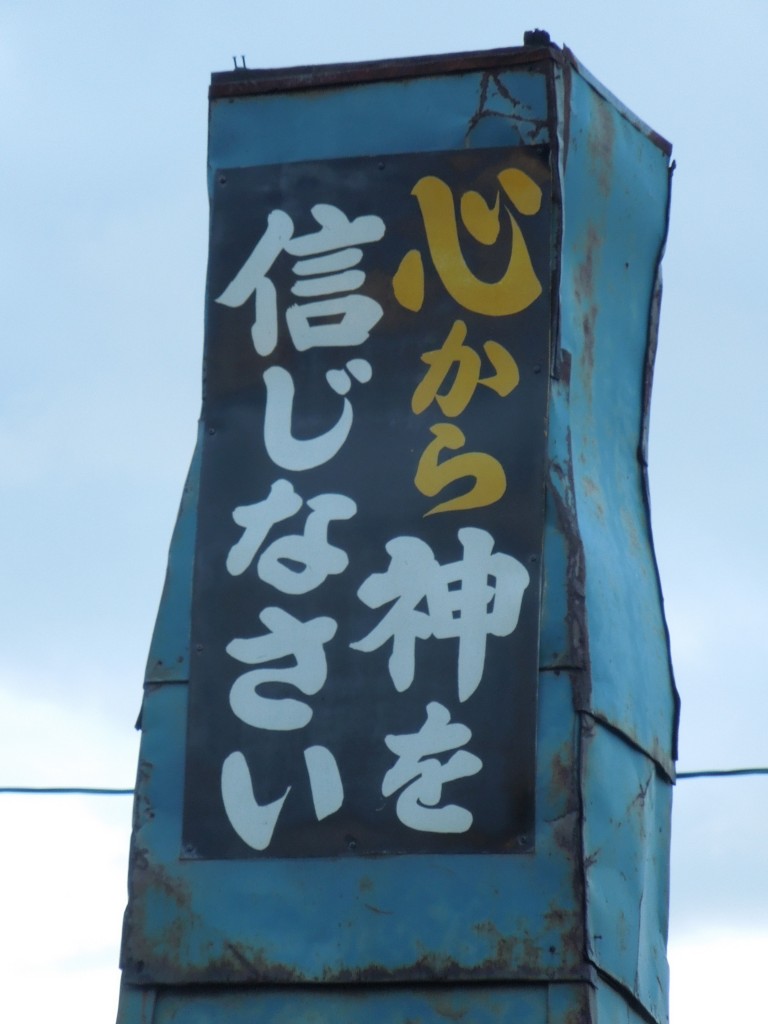

The all-year round chinowa at Hiraizumi's Hakusan Jinja

In recent days an observant reader may have noticed that I’ve posted entries on Shiretoko in Hokkaido, Shirakawa Sanchi in Aomori and now Hiraizumi also in Tohoku. What do they have in common?

The answer is that they are all World Heritage Sites. Japan has 16 in all, and I’m currently on a trip to visit them as part of my next book project. It’s a journey that is taking me from the northern parts of Hokkaido all the way down to Okinawa. But for the moment I’d like to concentrate on Hiraizumi.

Rise and fall of the Pure Land

Hiraizumi is all about the Pure Land, Amida’s Western paradise. The Buddhist deity made a vow that he would save all who believed in him, and the end of the Heian period saw an upsurge in devotion to his Pure Land. It was at this time, following a series of wars in the region, that Fujiwara no Kiyohira (1056 – 1128) set up a temple at Hiraizumi dedicated to the salvation of those who had perished in the fighting – regardless of to which side they belonged. Such was his attachment to Buddhism that he even included consideration for the souls of animals that had suffered in the fighting.

Over the next 100 years Kiyohira’s successors continued his vision of representing the beauty of the Pure Land. The result was a complex of villas and gardens built to the highest of aesthetic standards, such that the ‘Northern Capital’ came to rival Kyoto itself in terms of splendour.

It all came to a sad end after 1189 when the vindictive Kamakura shogun, Minamoto Yoritomo, turned on his half-brother Yoshitsune. The latter was seen as a potential rival, and he was forced to flee from Kyoto to the northern stronghold where he had personal connections. For a time he was shielded, but following the death of his protector he and his faithful companion Benkei were betrayed and killed by Yoritomo’s men. The shogun then ordered the destruction of the fiefdom that had stood up against him.

The site of Benkei's grave. He supposedly died defending Yoshitsune to the end, pierced with arrows.

Monument on the site of Yoshitsune's last residence, built on a small hill overlooking the countryside

View from Yoshitsune's last residence

Pure Land and Shinto

Advocates of the Pure Land are not noted for their Shinto sympathies, for the stress on submission to Amida leaves little room for dependence on other deities. But Tendai is an eclectic kind of sect, which embraces different forms of Buddhism including Pure Land and Zen meditation as well as esotericism and mountain asceticism. Hiraizumi was built in the twelfth century, before the split with the Pure Land sects, and it remains to this day a Tendai stronghold, Ever since its beginnings the sect had been sympathetic to the kami and a leading practitioner of syncretism. (Yoshitsune and Benkei, it’s worth noting, were Tendai men: Yoshitsune trained as a youth at Kurama Temple, north of Kyoto, and Benkei was a warrior-monk at the Tendai headquarters on Mt Hiei.)

The eto shrines at Hakusan Shrine, bearing animal pictures to denote the Chinese zodiac

Nowadays there are only the remains of the once glorious Hiraizumi heritage, but an enormous amount of research has been carried out on the settlements of former times. As a result it’s known that there were seven Shinto shrines at the time of its Pure Land glory.

One was the Hakusan Jinja, that predates the Tendai temples, and whose rebuilt modern counterpart still stands amidst the wooded precincts of Chuson-ji. As well as a wonderful Noh stage, I found it had a chinowa and a set of small eto shrines bearing animals to denote the Chinese horoscope. Both were unexpected.

‘Isn’t the chinowa usually for June?’ I asked the priest, who was in the shrine office doing some calligraphy.

‘Yes, but ours is for all the year.’ he answered without further elucidation.

‘The eto shrines are unusual,’ I ventured further. ‘I’ve only ever seen them before at Shimogamo Shrine. Are the ones here traditional, or have they been added in recent times?’

‘They are recent,’ he said. Since he clearly didn’t want to explain what had motivated their construction, I left him to continue with his calligraphy for I had other places to visit.

Torii lining the entrance way to the Takkoku temple

A cliffside temple

Ten minutes outside Hiraizumi, and not part of the World Heritage designation, is an eye-catching temple called Takkoku no Iwaya, founded in 801 by the imperial general, Sakanoue no Tamuraramo who subdued the ‘Northern barbarians’ known as the Emishi. It was built on stilts in the manner of Kiyomizu Temple in Kyoto, and set into the side of a small cliff. It’s a great example of just how syncretic Tendai can be.

Torii line the entrance to the temple. Ema are hung up for prayers. And a pamphlet invites people to pray by either clapping hands (Shinto style) or by holding their hands together silently (Buddhist style). The Buddhist deities are described in the kind of way you might expect of kami. Bishamon, for example, the principal deity, is said to invite happiness and to look kindly on those who pray for health, promotion or a good partner. Moreover, as a god of war he’s said to intercede forcibly on the petitioner’s side in conflicts.

Carving of a big Buddha set in the cliff face

Interestingly, the temple’s pamphlet says that Bishamon looks after those born in the year of the tiger; that Benten, also worshipped at the temple, is the patron of those born in the year of the snake; and that another temple figure, Fudo, protects those born in the year of the chicken. Does every year of the Chinese zodiac have their own Buddhist patron?

The head priest saw fit to finish off his pamphlet with a piece of political propaganda. In recent years, he said, the notion had arisen that Sakanoue was an agent of the central state based in Kyoto who had unjustly suppressed a local hero. This was far from the case, the head priest maintained, for in fact Sakanoue had acted as a liberating force who freed the people from an unjust regime which was making their life a misery. They had, and continue to have, every reason to be grateful to him.

From its foundation Tendai’s rationale has been to protect the interests of the imperial capital, and here in the twenty-first century it seemed the head priest was continuing to serve the cause. It was with a similar justification that according to mythology Jimmu embarked on his eastward passage of conquest to establish the fledgling Yamato state. Perhaps it’s no coincidence either that the Takkoku pamphlet was written about the very time that Bush and Blair were planning an illegal war for just the same kind of argument. It seems there’s a thin line indeed between intervention and imperialism.

Cliff temple of Takkoku no Iwaya, featuring here the raised platform of the Bishamon-do hall

In an article for The Daily Yomiuri, Naoki Matsumoto of Waseda University raises the question to his fellow countrymen of ‘When did we become Japanese?’ and goes on to answer his question with reference to the myths of the Kojiki (712) and Nihon shoki (720).

In an article for The Daily Yomiuri, Naoki Matsumoto of Waseda University raises the question to his fellow countrymen of ‘When did we become Japanese?’ and goes on to answer his question with reference to the myths of the Kojiki (712) and Nihon shoki (720).