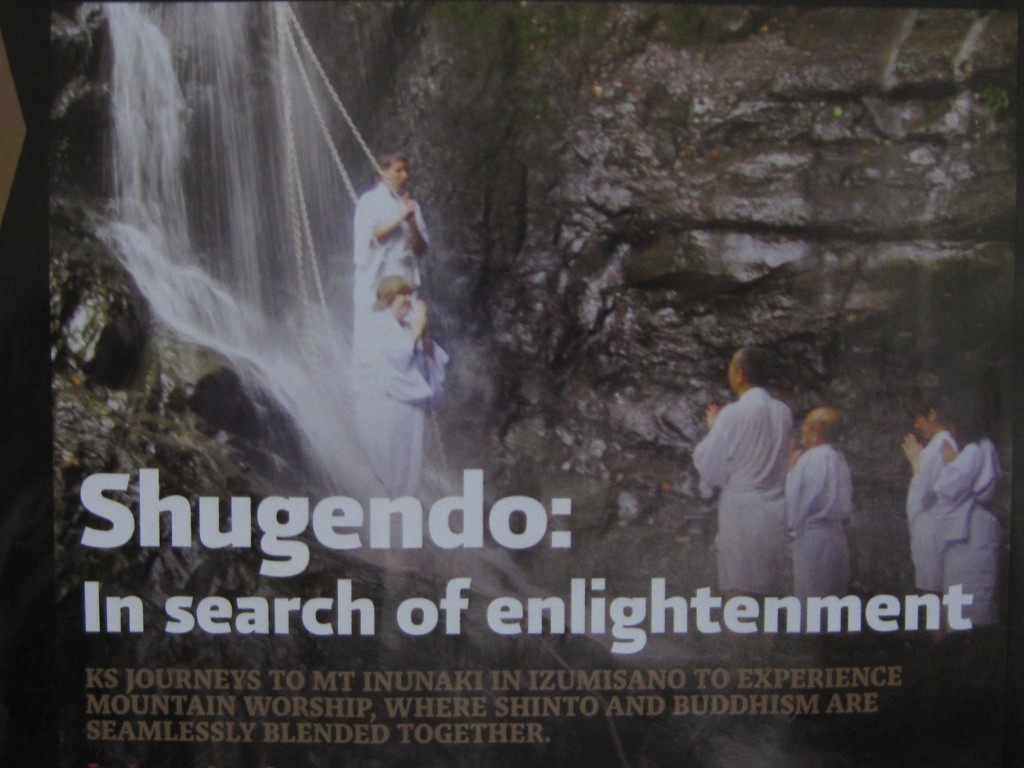

There’s a short article on shugendo in this month’s Kansai Scene, which can be read online here. It’s of particular interest because it describes an opportunity for foreigners to experience this Shinto-Buddhist blend of mountain asceticism for themselves.

Shugendo dates back some 1300 years, and was founded by the legendary seventh-century En no Gyoja (En the Ascetic). Practitioners, popularly known as yamabushi (literally, those who lie in the mountains), head into the hills to scale cliffs, fast, sleep in caves, stand under icy mountain streams, recite sutras and perform other rituals.

The rigorous activities are designed to heighten awareness and further spiritual development, so that practitioners come down from the mountain enhanced by the experience and able to help their community. The idea is that by getting ‘high’ one gets closer to the spirit world. It’s also a form of rebirth, for after leaving the everyday world the ego is broken down and forced to ‘die’, leading the way to a new and better self.

Two foreigners here seen doing cold water austerity on Mt Inunaki (Kansai Scene Dec. 2011 edition)

As a mountain lover, I’ve always found shugendo the most appealing of spiritual exercises – except for the bit where you get dangled over the edge of a cliff ! In her article, however, Bonnie Carpenter treats it in remarkably matter of fact manner.

At the top, Yoshida-san asked for participants for a more severe part of the training. Strapping on a thick white braided rope that encircled both shoulders, a novice prostrated himself flat on a rocky precipice overlooking the gorge, leaning as far out as he could possibly go. The assistant priest held up the novice’s back legs while the main priest holding the rope demanded, “Have you been good to your father and mother? Have you been working hard?” The novice responded with a nervous “Yes!” as he dangled precariously over the steep hills below. The intent was to put the supplicant under extreme physical and mental conditions, thus insuring a more honest response.

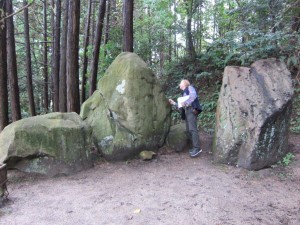

An intimidating cave opening, offering the possibility of returning to the womb and being reborn

On this occasion it seems the dangling over the cliff is voluntary. For Japanese who practise shugendo I believe it’s not. When I joined an outing myself, I made sure that there were no cliffs to be negotiated but still found myself panicking nonetheless at the prospect of entering a cave through a frighteningly narrow crack. As a claustrophobic, even enlightenment was not enticing enough for me to enter, and I had to join in the chanting of the Heart Sutra from outside the cave!

Shugendo was banned by the Meiji government as superstitious, but was revived after WW2 and made a strong come-back. Nonetheless it’s no longer the force it once was and opportunities to join are not easy to come by. Some of the groups used to be very secretive, and women were not allowed on several of the sacred mountains. Only in recent years has the religion become more open, and this opportunity advertised by the Kansai Scene is a rare opportunity for foreigners in Japan to be able to experience the tradition. I heartily recommend it.

- To try Shugendo, contact Inunaki-san Shipporyuji Temple at 072-459-7101/7043 or online in Japanese at the URL below. Reservations are required.

- The site offers training every third Sunday from March through November for groups of 20 or more for ¥2,000 per person. Smaller groups can be accommodated by consulting with the temple.

- Japanese ability is necessary, though you can bring your own translator.

- www.inunakisan.com

- www.kankou-izumisano.jp

***********************

For full details about shugendo, see Mark Schumacher’s online dictionary here. There’s also a useful site by a French practitioner who has established a base in Europe… http://www.shugendo.fr/en For ice-bathing misogi (cold water austerity) in Austria, see this youtube video. For an excellent NHK video introducing Shugendo at Dewa Sanzan, see https://vimeo.com/196561540

************************

Parade of yamabushi playing conch-horns

When not in the mountains, shugendo practitioners can be seen at temples (Shingon or Tendai) to which they are attached and where they often feature in fire festivals.

The sakaki branch is common in Shintō ceremonies. It’s used on altars, and it’s used as an offering to the kami. It’s used too as a vehicle into which the kami descends, and as a wand for purification. Performers hold sprigs in ritual dance, and it’s sometimes affixed to buildings or torii to signify the sacred quality. What is it exactly, and why should it be so sacred?

The sakaki branch is common in Shintō ceremonies. It’s used on altars, and it’s used as an offering to the kami. It’s used too as a vehicle into which the kami descends, and as a wand for purification. Performers hold sprigs in ritual dance, and it’s sometimes affixed to buildings or torii to signify the sacred quality. What is it exactly, and why should it be so sacred?

White horses

White horses

Postwar developments

Postwar developments