Izumo coast

Some of my favourite places are those enriched by myth, but which have escaped untouched from the ravages of modern life. Take the west of England, with its Arthurian tales, Somerset legends and Glastonbury mystique. Here in Japan the ancient byways of Kumano and the Yamato basin hold similar appeal. But even they can hardly compete with the allure of Izumo, on the ‘backside of Japan’. Put together with the prefectural capital of Matsue, one of the most attractive towns in Japan, and the area is a must-see for those who like to get off the beaten track. I’ve only made two short visits, but I hope to go for a longer spell next year.

Mythologically, Izumo is intriguing. It provides a dark alternative to the victorious Yamato narrative, which links the imperial line with descent from the sun goddess. By contrast Izumo is associated with Amaterasu’s brother, Susanoo no mikoto, the unruly storm god who throws a tantrum and causes trouble in the high plains of heaven. Amaterasu famously withdraws into a cave; Susanoo ends up an exile on earth where he wanders around the Hii River in Izumo. Amaterasu is female and determinedly Japanese. Susanoo is male and has foreign associations.

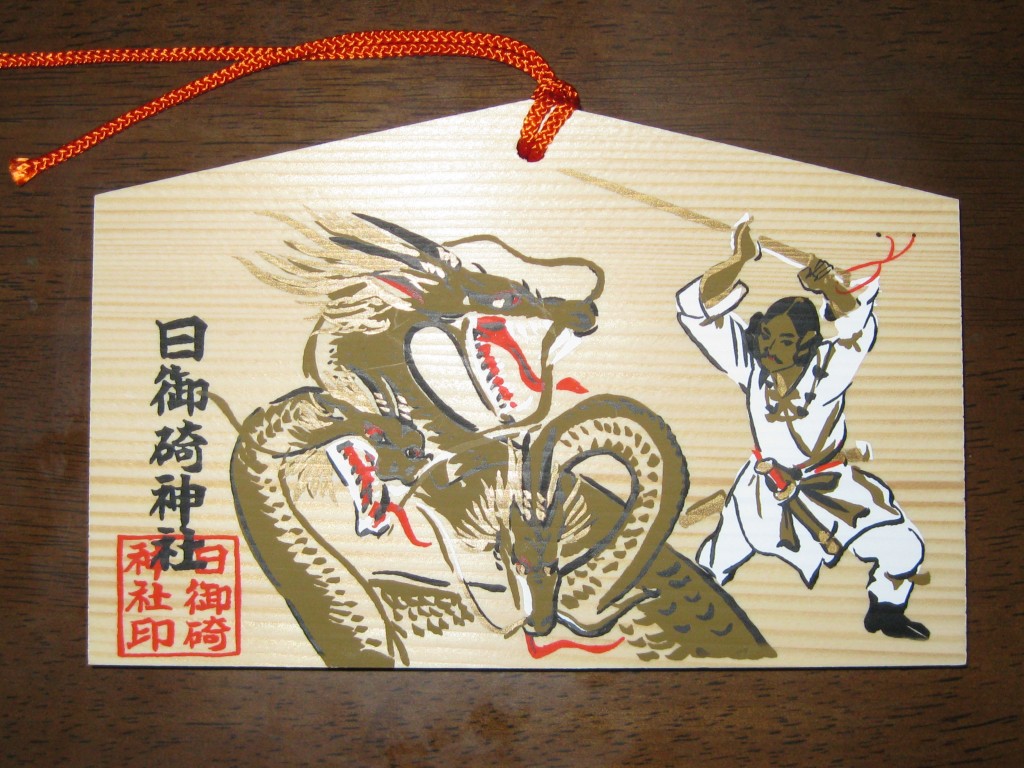

Most likely Susanoo represents Korean migrants, who came over from the kingdom of Silla and established a kingdom in the Izumo area. The rival Yamato kingdom, based near Nara, had ties to another Korean state, namely Paekche. No doubt when it came to writing the Kojiki (712), the Yamato myth-makers wanted to disparage Susanoo by having him defecate in Amaterasu’s rice fields, etc. In Izumo, though, he’s a folk hero who slew an eight-headed monster terrifying the territory and then founded the ruling dynasty.

The San’in region where Izumo is found occupies the Jpan Sea area of the Chugoku Region (Yamaguchi, Hiroshima, Shimane, Tottori, Okayama). It’s the shady side of the mountains (San’in = Mountain Shadows), with the southern part known as the sunny side (Sanyou = Mountain Sun). Significantly, there is a yin-yang significance in the Chinese characters. The Izumo region is all about ‘yin’ – darkness, moon, death, the subterranean and the unconscious.

Susanoo slaying the ‘yamata no orochi’ monster

Descent into the underworld

Yamato is represented by the sun goddess, Amaterasu; by contrast there’s something very dark about the nature of Izumo. Its name means ‘out of the clouds’, and the neighbouring area, from which Lafcadio Hearn took his Japanese name, is called Yakumo, ‘eight-fold clouds’. Compared with the sunny Pacific, it’s fair to say this is the overcast and gloomy side of Japan, as I know all too well from long years of living in Hokurirku.

It’s tempting to see a yin-yang opposition in the east-west contrast. The land of the sun, a yang element, is ruled over by a female goddess, whereas the land of darkness, a yin element, is ruled over by a male deity. The two are finely balanced, providing the energy field for the country as a whole.

I was only in the Izumo region for three days this time, but it was dark, rainy and overcast for virtually the whole three days. Swirling clouds. Mist hung on the hills. You have the feel that the veil between this world and the other is stretched thin. Ghostly shapes can form from the vapours at any time.

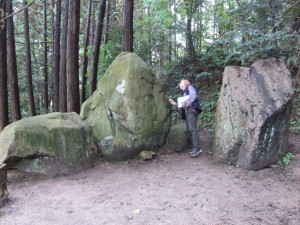

The climate is mirrored in the mythology, for the area is permeated with associations of death, darkness and the spirit realm. This is where Izanagi visited Izanami in the underworld after her demise, only to find her corpse rotten with maggots. You can see the boulder with which he supposedly stopped up the underworld at Yomotsu Hirasaka – though personally I found it lacking in atmosphere and, shockingly, it doesn’t even block the path properly!

‘Eight-fold clouds’ over Izumo

Peering into the underworld behind the boulder with which Izanagi supposedly stopped up the underworld

The setting sun

One of the great delights of my Izumo trip was discovering the delights of Hinomisaki Shrine. Serendipity is so much more enthralling than the expectation of something grand. The shrine is surprisingly large and well-appointed for such an out of the way place, stuck as it is on the end of the Izumo peninsula.

Spiritually it’s an intriguing shrine, for it honours both Amaterasu and Susanoo in separate haiden. Amaterasu is the primal deity, though it’s not the rising sun but the setting sun over the Japan Sea which is the focus. ‘We have a mandate to protect Japan at night,’ I was told by the couple manning the shrine office, though they were unable or unwilling to tell me who gave them the mandate.

There is also a shrine to Susanoo, who’s allegedly buried somewhere on the hill behind. According to local folklore, he hurled a kashihara branch up the hill and said that wherever it landed, his soul would rest.

The shrine does its rituals at sunset, which happened by chance to be the time we visited. There was a small group at worship in what seemed an unorthodox fashion, with an almost jazz-like riff on the taiko drum. I tried to find out from the people in the office what was going on, but they wouldn’t tell me anything more than it was special to the shrine.

Afterwards at a nearby restaurant we ate Izumo soba and watched the gathering darkness take hold. Here, in a land of mists and myths, it was good to know the shrine had a mandate to watch over us.

Izumo soba – three in one and one in three. The soba uses the whole grain, in contrast to the soba of other regions

Hinomisaki – small village, large shrine

****************************

(This entry draws on ‘Izumo as the Other Japan: Construction vs Reality’ by Klaus Antoni in Japanese Religions Vol.30 (1&2) p. 1-20)