A Kendo contest held at Kashihara Jingu

Brian Victoria, author of Zen at War, recently gave a talk in Kyoto about Zen terrorism in the 1930s. Brian is a Soto Zen priest, and his book has been hugely influential – as well as controversial. The book focuses on Japanese militarism from the time of the Meiji Restoration through the Second World War and the post-War period. It describes the influence of state policy on Buddhism in general, and particularly the influence on Zen which eagerly supported the military in its war of aggression. A famous quote is from a leading Zen figure, Harada Daiun Sogaku: “[If ordered to] march: tramp, tramp, or shoot: bang, bang. This is the manifestation of the highest Wisdom [of Enlightenment]. The unity of Zen and war of which I speak extends to the farthest reaches of the holy war.”

While reading about Brian Victoria’s book in an article in Japan Focus, I came across the following passage, which suggests a very conscious effort by Zen leaders to assimilate with Shinto in the Edo Period. It was a time of Kokugaku, when Nativists such as Motoori Norinaga were increasingly influential:

In the Edo period [1600-1867] Zen priests such as Shidō Bunan [1603-1676], Hakuin [1685-1768], and Torei [1721-1792] attempted to promote the unity of Zen and Shinto by emphasizing Shinto’s Zen-like features. While this resulted in the further assimilation of Zen into Japan, it occurred at the same time as the establishment of the power of the emperor system. Ultimately this meant that Zen lost almost all of its independence.

It seems then that the desire of leading Zen practitioners to align themselves with the Shinto cause brought identification with the nationalism of figures like Motoori (a noted China hater), which was exploited by Meiji leaders in formulating a State Shinto ideology aimed at bolstering the authority of the emperor they controlled. Acting on behalf of the nation was seen as an act of glorious self-sacrifice, by which the individual ego was sacrificed for the will of the emperor. It was an ideology to which both Zen and Shinto assented.

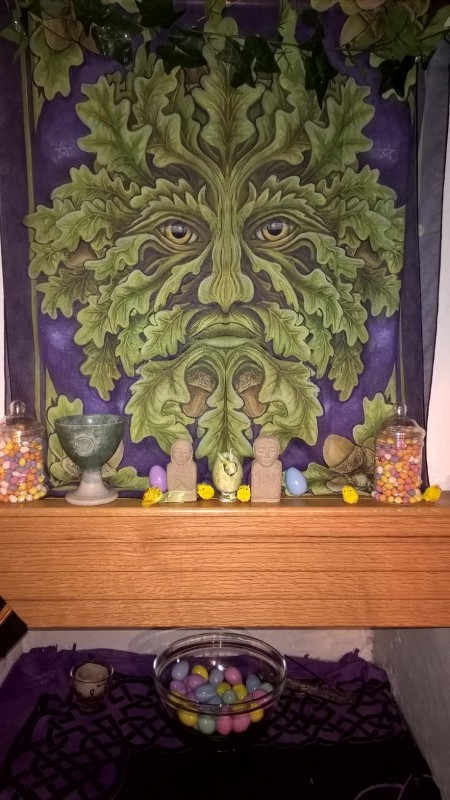

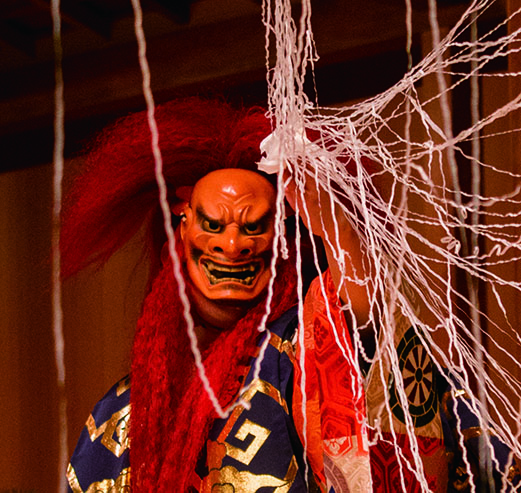

It is perhaps not coincidental then that both Zen and Shinto have been closely related to the development of martial arts. Zen was embraced by the warrior class, who took to its concern with mindfulness, self-discipline, and transcending the fear of death. Shinto was similarly allied to martial arts, not surprisingly given that ancient clan kami stood at the forefront of military conflict. The whole Yamato conquest was fuelled after all by notion of divine legitimacy. The swords that samurai treasured were imbued with animist spirit and buried with them.

When one thinks about it, there’s a military precision to the rituals of both Shinto and Zen. Anyone who has stayed overnight at a Zen temple will have noticed the emphasis on obeying orders, marching in line, and correctness in all things. Similarly those who have seen ceremonies at large Shinto shrines will have noticed the orderliness with which priests walk in file, the attention to detail in their rituals, and the hierarchical nature of the ranking.

It seems then that the military connection provides a key to understanding the commonality of Zen and Shinto. For those of us in the peace camp, it gives much to be concerned about. When I spoke to Brian Victoria about this, he suggested that the problem lay in the interaction of State and Religion. Regardless of the leanings of a particular religion, when it becomes allied to the State through seeking patronage and protection, it necessarily becomes a servant of State in times of war. Christianity has done it, Islam has done it, Judaism, Hinduism and Buddhism have done it. Perhaps there then lies the lesson in all this, and perhaps the hermit tradition of Daoism is the perfect response!

Sword skills displayed at Shimogamo Jinja

Zabuton cushions laid out in a Zen temple meditation room. Each monk is allotted one tatami and small cupboard space, similar to life in a barracks.

Obeisance lies at the heart of Shinto – and Zen

Shaved heads and lined up in a straight row…

Priests parading in single file are a common sight at Shinto ceremonies.