Buddhist priests outnumber their Shinto counterparts – and historically they held more authority

A book I came across recently (Visions of Power, Imagining Medieval Japanese Buddhism) discusses the attitude of early monks to the kami. By and large, the Buddhists saw themselves as possessing greater power through the truth of their teaching. Though their attitude was largely one of respect and devotion, there are many legends of monks converting local gods to Buddhism, in return for which they are allowed to establish monasteries and granted protection. In some cases the monks actually punish the kami for not carrying out their role of protector properly.

Gohei offering in a Tendai temple

At one time there was hostility among kami supporters to the imported religion, but this was soon suffused into mutual recognition. A famous medieval account tells how Emperor Shomu asked the Buddhist priest, Gyoki, to offer a relic of the Buddha at Ise. On the seventh day after the offering, the voice of Amaterasu was heard to say that thanks to the monk’s devotion she had just achieved salvation. Thereafter the emperor dreamt that Amaterasu was none other than the Buddhist deity, Dainichi (literally, Great Sun).

A later Buddhist sect, Zen, became associated with Sugawara no Michizane, who was one of the last to go to China to study in Heian times. The Chan master Wuzhun Shifan (1177-1249) is said to have transmitted his patriarchal robe to Michizane, who posthumously became the kami Tenjin. Like other kami, Sugawara’s spirit was integrated into Zen as a protector of temples, though it was thought he needed Buddhist instruction to achieve true enlightenment.

Enni Ben’en, founder of Tofuku-ji, was visited by Michizane in a dream and told to go to China to study meditation. He did, spending six years there and returning to spread Zen in Kyushu (he also brought back noodles, namely udon).

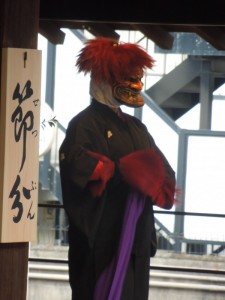

Hachiman dressed as a Buddhist priest in search of enlightenment

In China the three teachings were of Buddhism, Confucianism and Daoism. In Japan Daoism was replaced with its local equivalent, Shinto. The worship of kami by Buddhist priests has been viewed as a ‘skillful means’ by which to achieve their ends. Some believed they were ‘masters of the kami’, while others may have been agnostic (as are many today, calling themselves ritualists rather than believers). Nonetheless the legacy is clear.

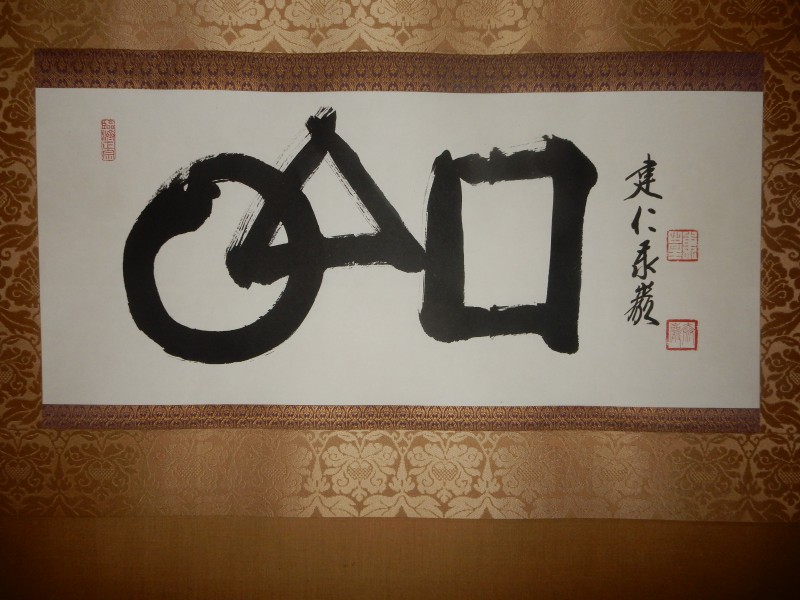

As I’ve come to see on my round of Zen temples, far from ‘Nothingness’ the Zen imagination is peopled by a populous universe. As if the eight myriad kami of Japan were not enough, temple statues include a whole range of deities drawn China and India, ranked into four groupings:

- Enlightened beings known as Nyorai (historical Buddha i.e. Shakyamuni, Amida Nyorai, Dainichi Nyorai, Yakushi Myorai). .

- Boddhisattvas (bosatsu in Japanese), notably Kannon, Jizo and Miroku

- Myoo (Fudo Myoo being the most common)

- Protectors known as -ten, such as Bishamonten, Marisihiten, Benzaiten

In a reversal of what one might expect, the native kami were ranked below the imported deities in shinbutsu-shugyo syncretism. The kami were already part of the spiritual landscape, so they had to be fitted in somehow. Only by becoming Buddhist could they advance, one of the most famous cases being Hachiman bosatsu (a kami-cum-Bodhisattva). No wonder that in Yoshida Kanetomo (1435-1511) a counter-movement arose to reverse the order and assert kami as superior to Buddhas by dint of being Japanese. The nationalist line was taken up by Motoori Morinaga and the Nativists of the eighteenth century. It’s a legacy which is still being played out today.

Yoshida Shrine in Kyoto, which led the fight-back against Buddhist domination

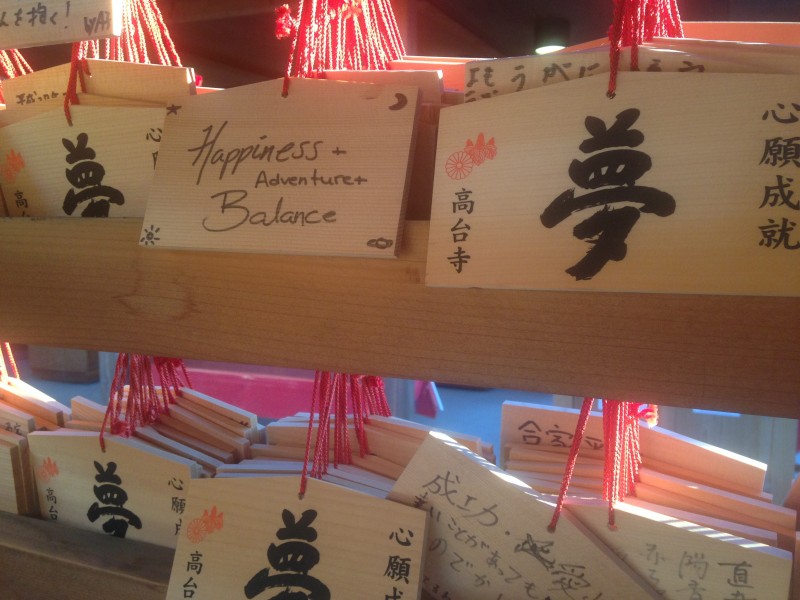

Yes, it’s that time of year again, and the shrines and temples will be open on Feb 3 (some on Feb 2) for bean throwing to dispel the demons that accumulate in the long dark nights of winter.

Yes, it’s that time of year again, and the shrines and temples will be open on Feb 3 (some on Feb 2) for bean throwing to dispel the demons that accumulate in the long dark nights of winter.