In the days leading up to the New Year, it seems right to turn attention to what will be the nation’s no. 1 most popular spot for shrine visiting. That’s just what The Japan Times did yesterday with its celebratory article below. It’s timely too, since Green Shinto recently did a piece on Meiji’s burial mound here in Kyoto, together with an example of the emperor’s verse (one of 100,000 he composed!). (For a previous piece on the Meiji Shrine forest, see here.)

Amidst the raging storms of life

Never flinch, o heart of man —

No more than the wind-tossed pine

Deep-rooted in the rock

— Emperor Meiji

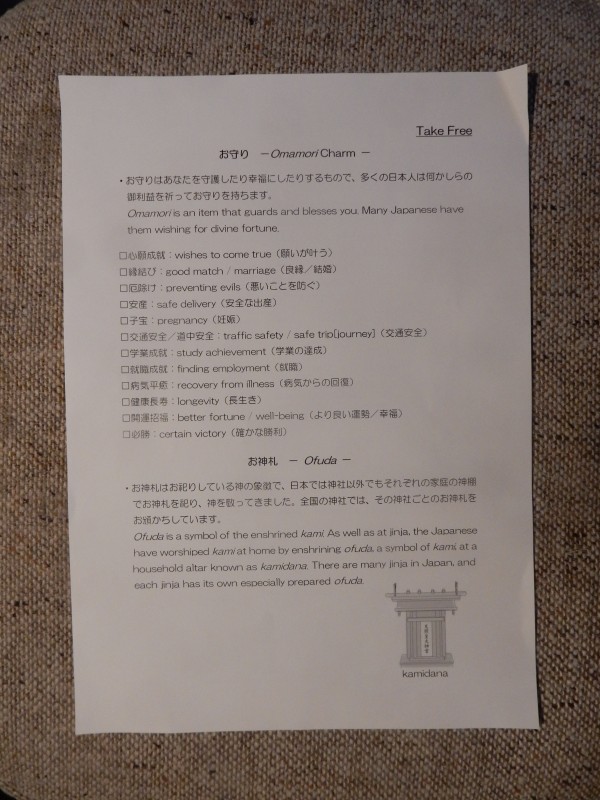

This classical waka poem was written, in English, on the omikuji (paper fortune) that I recently drew when I visited the Tokyo’s Meiji Shrine, a Shinto shrine dedicated to Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken.

Emperor Meiji was known for his love of composing waka, having left behind a collection of about 100,000 poems for his people. His consort, Empress Shoken, is also believed to have composed around 30,000 of her own. Out of both the Emperor and Empress’ works, 30 were picked to be used for omikuji [fortune slips] — to become guiding words of wisdom for our daily life.

“Written omikuji (at shrines) usually represent either kichi (good luck) or kyō (bad luck). Ours, however, feature traditional waka poems written by either the Emperor Meiji or the Empress Shoken,” says Miki Fukutoku, manager at Meiji Shrine’s public-relations department. “It’s something very particular to and only available at our shrine.”

As a relatively new place of worship, established less than a century ago in 1920, Meiji Shrine was originally based around the concept of wakonyōsai — a belief that treasured the Japanese “soul,” while still embracing influences from the West. Its unusual omikuji, therefore, is not the only unique feature of the shrine.

“People tend to think Meiji Shrine is just the main shrine; however, it’s actually about a much larger area that includes both inner and outer gardens,” Fukutoku says. “The main shrine (in the inner gardens) is symbolically traditional Japanese (by design), where you worship and pay your respects to the spirits. The outer garden is more Westernized — it contains the Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery, which houses 80 paintings, and reflects the life of Emperor Meiji, who promoted friendly relations with overseas countries. The symmetric alignment of ginkgo trees in front of the gallery is believed to be designed after the Palace of Versailles.”

The Treasure Museum of the Gaien gardens perhaps exemplifies this blend of Japanese and Western influences. Its architectural design resembles Shosoin, a treasure house that belongs to Nara Prefecture’s famous Todai-ji Temple. Unlike the temple, however, Meiji Shrine’s Treasure Museum is not made of wood but of reinforced concrete.

The shrine’s three main areas — Naien (inner) precinct with shrine buildings; Gaien (outer) precinct with the Meiji Memorial Picture Gallery and sports facilities, including the country’s second-oldest baseball stadium Meiji Jingu Stadium; and the Meiji Memorial Hall, a wedding hall — are also amid 700,000 sq. meters of lush forest. Around 170,000 trees of 245 different species were arranged by landscape architect Seiroku Honda (1866-1952) and his assistants Takanori Hongo (1877-1945) and Keiji Uehara (1889-1981), who famously refused the proposal of the then-Prime Minister Shigenobu Okuma (1838-1922) to exclusively use cedar. Honda wanted to create an evergreen forest, and cedar, it turned out, was an unsuitable tree for the area’s soil.

“In 2011, we surveyed the species living in the area as part of our preparations for the (shrine’s) 100th anniversary,” Fukutoku says. “This man-made forest was designed to last forever, so we’re keeping a record to see whether it’s evolving according to plan. The research so far says that, in terms of biodiversity, the forest contains far fewer alien species compared with its surrounding areas of central Tokyo.”

That abundance of local nature has attracted visitors other than worshippers to the shrine, where many rare species such as jewel beetles, kingfishers and northern goshawks are commonly seen among the trees and plants. It is home to Japan’s endangered golden orchid and kanto tanpopo, a native dandelion protected from invasive foreign species by the barrier of the forest.

“The forest is now about to reach the end of Honda, Hongo and Uehara’s protocol and experts say it will remain this condition for some time, since camphor trees can live live 300 to 400 years,” says Fukutoku. “We won’t live for that long, though,” she continues with a laugh, “so, the next plan will be passed on to the next generation.”

Fukutoku says that despite all these attractions of Meiji Shrine, the number of non-Japanese visitors has only gradually increased over the years, even though she also says, “A visit to Meiji Shrine could be an easy way of introducing yourself to Japanese culture.”

“The shrines in the suburbs may offer a more authentic atmosphere, but we’re more accessible — even for someone like President Barack Obama, who came to visit last year. It’s in the center of Tokyo, but it is also suddenly within a forest and a sacred space of worship.”

The shrine’s most important festival, the Reisai (Autumn Grand Festival), held on Nov. 3 to commemorate Emperor Meiji’s birthday, invites ambassadors of many countries to view various traditional performances. Yet even though this is the most significant day for the shrine, Fukutoku says it is the upcoming new year season that is always the busiest time of the year.

Of the 10 million visitors it receives each year, around 3 million head to the shrine for hatsumōde, during the first few days of the year. So it you’re thinking of heading there, too, there are a few things you might want to keep in mind.

Meiji Shrine has three entrances — Harajuku-guchi, Yoyogi-guchi and Sangubashi-guchi. For hatsumōde (NewYear when it is at its utmost crowded), Harajuku-guchi is usually the only entrance open. This is mainly to help control the crowd, but, as Fukutoku explains, it also leads visitors to follow the proper path to the main shrine.

“Since Harajuku Station was built before Meiji Shrine, it’s obvious that most visitors arrive from Harajuku-guchi. That’s why nearby Omotesando is named so, ‘omote‘ means ‘front’ and ‘sandō’ means ‘visiting road,’ ” continues Fukutoku. “The Harajuku-guchi torii gate is therefore also the biggest one out of the three entrance gates (besides the dai-torii (large size gate) between Harajuku-guchi and Yoyogi-guchi). It’s usually a one-way path, but (if you take it), you will see all noted sights of the shrine.”

In 2020, the year of the Tokyo Olympics, Meiji Shrine will celebrate its 100th anniversary since its enshrinement and it faces renovations that Fukutoku says should help welcome more international visitors. “The preparation (for the 100th year) was scheduled to have started in fall, so we’re a little bit behind,” she explains. “But we are planning to make the area barrier free. Also, there are plans to repair the main shrine, which occasionally leaks through the roof during rainfall. That’s where the souls of Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken are enshrined — it’s the most essential part of the Meiji Shrine.”

Meiji Shrine is open on New Year’s Eve from 6:40 a.m. through to 7 p.m. on New Year’s Day. It is then open from 6:40 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. on Jan. 2, 3 and until 6 p.m. on Jan. 4. For more information, visit www.meijijingu.or.jp/english/index.html. For suggestions on where to visit during New Year in Tokyo, including a New Year’s Eve parade of people dressed as foxes, see here.

An oasis of greenery in a city of concrete

A homemaker cooks, cleans and takes care of the household-related issues that are necessary to keep a family running. But unlike “ordinary” people with “real jobs,” she does not get paid.

A homemaker cooks, cleans and takes care of the household-related issues that are necessary to keep a family running. But unlike “ordinary” people with “real jobs,” she does not get paid.

Sake ‘Cask Opening’ Ceremony – 11.30 AM

Sake ‘Cask Opening’ Ceremony – 11.30 AM Mochi Pounding – 12.00 PM

Mochi Pounding – 12.00 PM