One of the seven gardeners employed to sweep the paths (the leaves are recycled back into the woods). There are 20 gardeners in all, who monitor the growth, remove dead wood and protect the trees from disease.

It’s a a mixed forest of 160,000 trees covering a huge seven hectares and housing one of Japan’s most popular shrines. It contains 240 species and and a flourishing wildlife that includes hawks, fish and tanuki racoons. It’s a shrine grove praised for its beauty and spirituality, set amidst a sprawling urban conglomeration of concrete and tarmac. But what makes it particularly special is that it’s an artificial creation, planted a hundred years ago (1915-20) by some 110,000 volunteers.

To mark the centenary, NHK ran a special the other evening on the Meiji Shrine forest. But first, a bit of background information. After Emperor Meiji’s death in 1912, the government determined to commemorate his role in the historic Meiji Restoration with a shrine. The location centred on an iris garden which he and his wife had had been fond of visiting, and the shrine was built in cypress and copper. The construction was a national project, mobilizing youth groups and civic associations throughout Japan. It was completed in 1921, destroyed during WW2, and rebuilt in 1958.

To complete the surrounds, trees were donated from all parts of Japan, and the grove is cherished for its role in displaying Shinto’s affinity with nature. (The woods are for the enjoyment of the kami and off-limits to visitors.) Here is the shrine’s official description:

Meiji Jingu’s forest was created in honour of Emperor Meiji and Empress Shoken, for their souls to dwell in and with every tree sincerely planted by hand. This forest was carefully planned as an eternal forest that recreates itself. Now after about 90 years it cannot be distinguished from a natural forest, inhabited by many endangered plants and animals.

One point of interest is Kiyomasa’s well, probably Japan’s best-known power spot. It was created by Kato Kiyomasa, a general under Hideyoshi who invaded Korea in the 1590s. In 2009 the well was declared to be particularly efficacious in wish-fulfilment by popular tv personality and fortune-teller Shimada Shuhei, since when it’s been inundated with visitors.

Ironically, the Meiji forest which is now held up as a prime example of Shinto’s concern for nature came at a time when Shinto groves were suffering terrible depletion. This was during the merger of shrines which took place 1906-1923, when the total number was drastically reduced from 193,000 to 110.000. The loss of the shrines was accompanied by the destruction of the surrounding groves.

By contrast the Meiji forest stands as a flourishing oasis of greenery amidst the urban sprawl of Tokyo. It’s a ‘people’s forest’ that sustains wildlife, purifies the air and offers hope for the future. In its conservation of the forest, the Meiji Shrine shows how Shinto could put green rather than national concerns at the forefront of its agenda. In this regard it’s interesting that the shrine brochure chooses not to end on a note of universalism but by asserting how the forest ‘helps to pass down our traditional Japanese value for nature from generation to generation’.

*************************************

Information from Aike Rots ‘Forest of the Gods’, PhD dissertation at the University of Oslo.

To add intrigue to their coverage, NHK dubbed the forest a mystery and subtitled the programme ‘100 years of a grand experiment’.

An illustration of the Meiji Shrine layout. 90% is woodland or water, off-limits to visitors and for the enjoyment of the kami.

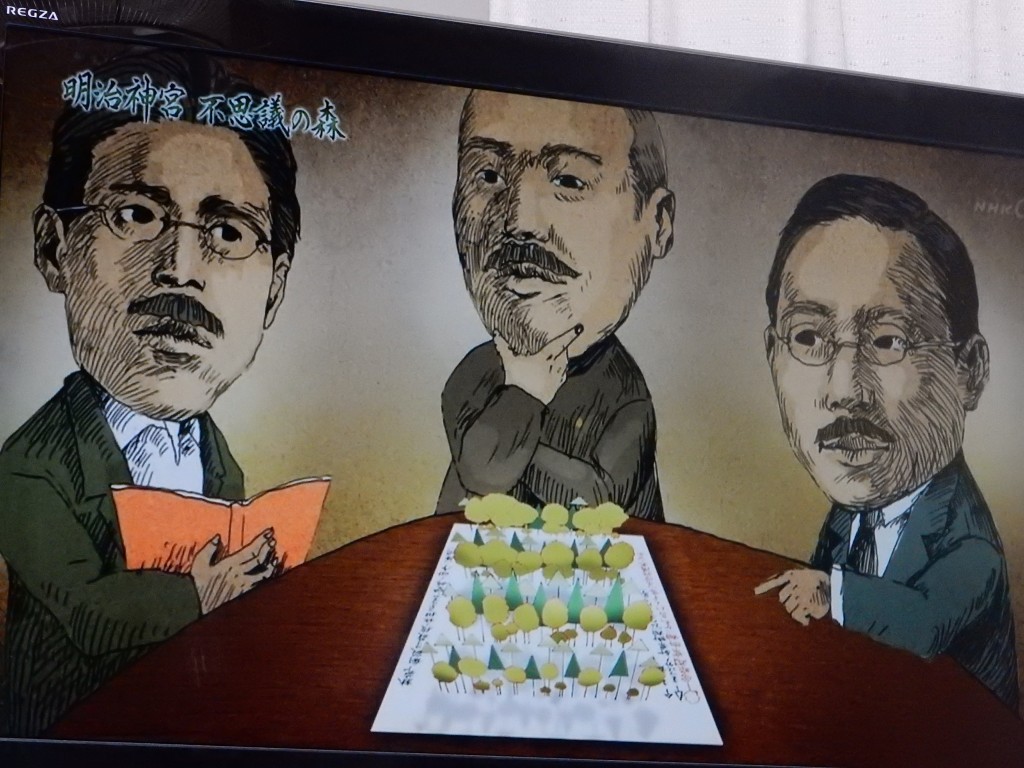

The three people who planned the forest, and the diagram they drew up showing how the woods would look after 50 and 90 years.

How the area looked before the woodland was planted

How the area looks now, and the contrast with its urban surrounds

The woods are home to hawks, owls and other birds rarely seen in the middle of an urban development.

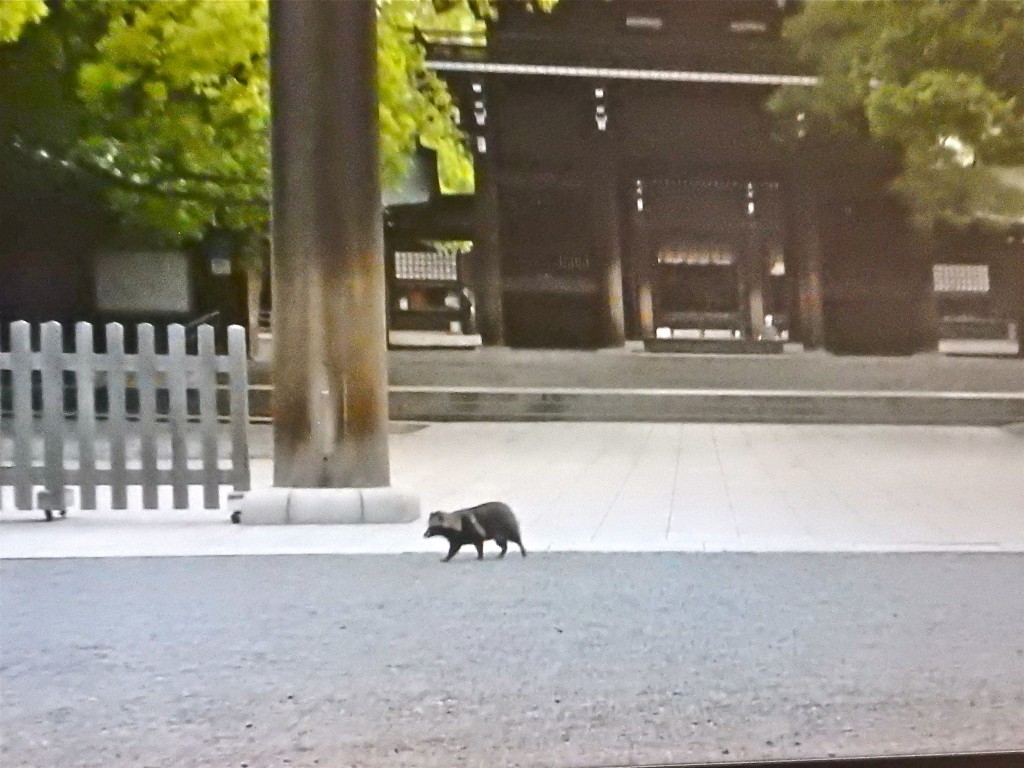

A tanuki enjoys the chance for an evening stroll in the woods

Not only the woodland, but the water too has flourishing wildlife.

After all the visitors have left, the tanuki takes the opportunity to pay respects at the shrine and give thanks for its woodland blessings.

John D —

A short note . . . I’m including a link to your story in an archive/republish story I did in 2016 on the Meiji Jingu — which will be published on gardensoftheworld.org — in the coming days. It was originally done for Ecology Global Network/ecology.com — which has in meantime gone completely dark.

I am also going to include a link to the upcoming Asie-Sorbonne Workshop . . .

The good work and earnest efforts of individuals such as yourself are ever more important for us all . . . and so deeply inspiring. Take care. Stay safe. Thank you.

Thank you, Janis, for the kind words and for the links. That is certainly gratifying to know,and I wish you too all the best in your endeavours.