1) How and when did you get the calling to become a Shinto priest?

Dougill Sensei, first may I say many congratulations regarding your excellent blog: Green Shinto, and also thank you so much for your recent Omairi/ shrine visit to Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America.

As for my personal history: I have the longish involvement as the teacher of Aikido, over 40 years… However even from before I found the Aiki training, I was very interested and very drawn to Shinto and the consciousness behind Natural Spirituality. I was living in Southern California—in my younger days I was the artist and the surfer. In any case I was doing my best to learn about Shinto when in the early 1970’s I was gifted with Nahum Stiskin’s excellent book The Looking Glass God. That book was really pivotal for me as I strongly resonated with Mr. Stiskin’s overview of Shinto. I then began to practice misogi shuho as best as I could and was very devoted to the daily practice of a simplified form of Shinto Meditation that I learned through Aikido and Macrobiotics.

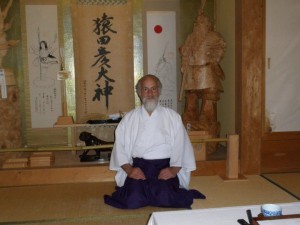

Original Tsubaki shrine in Stockton, Ca., 1987-2001

In 1980 I relocated from Southern California to the Pacific Northwest with the goal of making the shrine for Gyo [ascetic practice] in a natural setting. In those days I was also very involved in the Shukyo (modern Shinto). In the 1980’s I was very popular as the instructor of Aikido and quite active to conduct the seminars…I was saving all proceeds with the goal of making a shrine. Then in 1987 I learned about Tsubaki America shrine in Stockton California. I was able to meet Rev. Iwasaki who was the priest of the shrine at that time. I asked Rev Iwasaki at our first meeting if it was possible for me to become the Shinto Priest —- he told me it was quite impossible in the world of Jinja Shinto, but it was possible for me to learn better how to care for my shrine.

Yamamoto Yukitaka, Sendai Guji, who introduced Shinto to America

When I traveled to Tsubaki Okami Yashiro the first time it was quite an epiphany for me– I had visited many shrines on previous visits to Japan but visiting there was quite profound for me — I felt I had journeyed to the heart of the world and instantly felt more at home than I had ever felt before in my life. Yamamoto Yukitaka Guji (the 96th generation High Priest of the shrine) and all the kannushi [priests] of the shrine were very kind to me and began to share many things with me —I was something of a pet to the shrine priests. I did not think then to ever have the license of the Shinto priest but I was so impressed with Tsubaki Okami Yashiro and the work of the kannushi that I was very serious to learn all I could. I felt without fail that the Jinja Shinto I saw there was the highest expression of human beings cooperating with Okamisama and Divine Nature.

2) What did your training consist of exactly?

Well, as I mentioned, in the 1980’s and early 1990’s although I did not think I could receive the Kannushi Shomeisyo/ Priest License, I was very active with Shinto Meditation and purification practices…also I had built the shrine and wanted to learn how best to care for the enshrined Kami…so I was traveling to Tsubaki Okami Yashiro 2 or 3 times each year and staying for a few weeks while receiving intense instruction from the various shrine priests. During these years I could travel with Yamamoto Yukitaka Guji and also visit many shrines guided by the Kannushi of Tsubaki Okami Yashiro.

Tsubaki Shrine in Mie Precture

In-between various lessons I would stay in the samushyo (shrine office) and observe various phases of shrine operation—I could also help prepare for various events and ceremonies. It was a really magical period and I am a little nostalgic to think of those days. The shrine priests and staff were incredibly kind to me and patient with me as well— my responsibilities were not so great. I was able to totally focus on my training and working to know Sarutahiko Okami.

This was the time period of my building Kannagara Dojo/ Jinja for my own training in Gyo and to introduce other Aikido people from around the world to the practices of Jinja Shinto. I was also of course studying Kojiki and kotodama, as well as practicing daily Misogi Shuho (purification) in free flowing water (I could practice since 1975 or so, and every day from summer of 1992 until the present).

Misogi on the grounds of Tsubaki America. Rev. Barrish is second from the left, with Yamamoto Yukiyasu Guji on one side and Rev. Anne Evans on the other

In any case at some point Yamamoto Yukitaka Guji decided I should receive the Jinja Shinto License…I still remember very vividly receiving the phone call and having that discussion. At that point I trained in saho (manners of conducting various ceremonies) for an additional month or so and was able to receive the entry level license in 1995. Over the next few years I began to conduct ceremonies, mainly for Aikido people, while continuing my training at Tsubaki Okami Yashiro in Japan. I became more and more busy as the Shinto priest, conducting many many ceremonies while continuing to try to improve myself… I was able to become the Gon-Negi/ assistant senior priest and then the Negi/ senior priest.

3) Before the establishment of the Tsubaki branch shrine, I believe you operated your own shrine. How did that work?

The history of Tsubaki Grand Shrine in America is that it was first established in 1986 in Stockton California – a non-profit organization was begun and a series of Shinto Priests from Tsubaki Okami Yashiro (Tsubaki Grand Shrine in Japan) served at Tsubaki America introducing Jinja Shinto in North America.

In 1992 I was able to build Kannagara Dojo and Jinja independently to enshrine Tsubaki Okamisama, and as a shrine for Gyo (training) in such things as Misogi Shuho (water purification), Chinkon Gyo-Ho (Shinto active meditation) and Aiki movement. In 1995 I became the fully licensed Shrine Shinto Priest and we began to use the name Tsubaki Kannagara Jinja for my shrine. A few years later I received the license of Guji of Tsubaki Kannagara Jinja….Yamamoto Yukitaka Guji was really proud of our accomplishment here and would always introduce me as Kannagara Guji.

The present shrine buildings

Around 1997 we were “discovered” by the community of Japanese people living in the Pacific Northwest and became busier and busier as the Jinja Shinto Shrine. Then in 2001 the Matsuri Foundation gifted 17 acres of land adjacent to Tsubaki Kannagara shrine grounds to the Tsubaki America entity. At that time the decision was made to combine Tsubaki America and Tsubaki Kannagara Jinja at the sacred site of Kannagara Jinja.

In May of 2001 we closed the Stockton shrine and began to operate as America Tsubaki Okami Yashiro (Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America). We used the proceeds of the sale of the Stockton property to build the Kaikan (guest house) and we began to build the Sukeikai (members group).

4) In establishing the Tsubaki branch shrine, what were the biggest challenges and obstacles you faced?

Well, we are always day by day doing our utmost to improve ourselves and our Jinja. When we became more and more active as the Jinja in the late 1990’s, we had to begin to learn how to create and organize systems of operation…of course we have the ideal example and support of Yamamoto Yukiyasu Guji, the 97th High Priest of Tsubaki Okami Yashiro. Also my wife who is Japanese and has the strong business background works tirelessly as shrine manager–always seeking to improve our operations and the experience for sanpaisya (worshippers). Because of her inspired hard work, I am free to concentrate on gyo and ritual which remain my prime interest—-so we are constantly trying to evolve. Of course our challenges are to operate, support and care for the Jinja, as well as do our utmost to meet the spiritual needs and care for the shrine visitors in happy times and sad times.

A full house at Tsubaki Grand Shrine of America

For Part Two of this interview, please click here.

Had lunch with Pat Ormsby today, Shinto priest and environmentalist, who told me the history of the Asakawa Konpira fight to protect the mountain on which it stands at Takao on the fringe of Tokyo. The leading role the shrine played is an inspirational story of the direction that Shinto as a whole could take, if it is so willed. It’s a story I hope to get up on Green Shinto in full.

Had lunch with Pat Ormsby today, Shinto priest and environmentalist, who told me the history of the Asakawa Konpira fight to protect the mountain on which it stands at Takao on the fringe of Tokyo. The leading role the shrine played is an inspirational story of the direction that Shinto as a whole could take, if it is so willed. It’s a story I hope to get up on Green Shinto in full.