In May 2005 I visited the two main Oomoto bases, their spiritual centre at Ayabe and the admin and training centre in Kameoka. My main impressions? Devotion, elegance, and money. Let me explain.

Priests warming up before the ceremony

Ayabe was hosting a festival, and there must have been well over 3000 people there for speeches and services on an estate that was huge and expansive. The grounds were artistically laid out, with a Heian type pond garden and small stream. The buildings were enormous; the main hall held 730 tatami, which is nearly as many as some of the great Buddhist temples in Kyoto. There were well apportioned buildings dotted around the grounds, which made me wonder how on earth this was all funded.

Even more striking in a way was the Kameoka base, which is housed in the former castle of Akechi Mitsuhide –the daimyo who killed Oda Nobunaga. It dominates the centre of Kameoka, with a moat and parts of the old wall still standing. Inside are plum groves, open spaces, a shrine building, and large admin buildings. Usually national universities or large corporations occupy such sites; how did Oomoto manage, I found myself wondering.

Family praying in perfect harmony

I talked with a couple of priests, who were friendly and open. They talked of the founder called Deguchi Nao who was possessed by a spirit in 1892, following which she miraculously began to write down teachings and prophecies. The man who is seen as cofounder of the religion, Deguchi Onisaburo, had some kind of vision to meet up with her and further her teachings. He married her daughter and produced 81 volumes of his own about his shamanistic travels in the spirit world. The present head of the sect is his granddaughter.

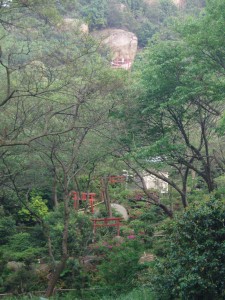

The central spirit of the sect is Ushitora no Konjin, not mentioned in Kojiki, which translates as something like Mixed Deity of CowTiger. It’s an intriguing hybrid to try and picture mentally. The sect says it is monotheistic, that all spirits are basically one and the same, and that all religions come from the same source. It also lays great stress on art as a way to the divine, and there’s a strong artistic touch to the grounds and atmosphere.

Elegant temizuya

Oomoto has played a significant part in opening up to foreigners. The founder of aikido, Ueshiba Morihei, was once associated with the sect, and in more recent times Alex Kerr was involved with them operating cultural seminars for foreigners. The big question for me was the relationship to Shinto, and for this I was referred to the official website which had this to say:

Q-How is Oomoto like Shinto?

A-The importance of harmony among nature, humans, and gods is a key belief of both. Oomoto’s rituals, architecture, and vestments are based on the ancient original practices that became known as Shinto.

Q-How is Oomoto different from Shinto?

A-Shinto is polytheistic, believing there are many gods – or kami. Oomoto teaches that many kami do exist, but they all come from the same Supreme God of the Universe, so in effect there is just one God. When Oomoto followers pray to a particular kami by name they understand this is just one manifestation of the single God. Even the name “Oomoto” emphasizes this point. It translates as “Great Source” or “Great Origin.”

http://www.oomoto.or.jp/English/enFaq/indexfaq.html

Aesthetically pleasing offerings

$5.00

$5.00