March 11, 2011 was a devastating day for Japan. Over 18,500 people perished in the gigantic tsunami that swept over the coastline of Tohoku in the country’s north-east. What’s more it led to a nuclear meltdown, the consequences of which are still on-going. Ghosts of the Tsunami, as indicated by the title, concerns itself with the natural disaster, not the man-made one.

March 11, 2011 was a devastating day for Japan. Over 18,500 people perished in the gigantic tsunami that swept over the coastline of Tohoku in the country’s north-east. What’s more it led to a nuclear meltdown, the consequences of which are still on-going. Ghosts of the Tsunami, as indicated by the title, concerns itself with the natural disaster, not the man-made one.

The book, published in 2017, was written by Richard Lloyd Parry, correspondent for the UK’s The Times. It is remarkable in many ways, not the least for the technical feat of turning a sustained investigation of despair and destruction, of grief and mourning, into a compelling read. Based on interviews with both bereaved and survivors, the subject matter is a potential minefield, for a single inappropriate or insensitive statement could blow up in the writer’s face.

Even more astonishing, the book turns out to be a page turner because of the sense of immediacy. The focus on real-life individuals provides a feeling of involvement, and the multiple narratives are skilfully handled in such a manner that the reader is constantly curious as to what or who will be featured next. There’s even a sense of mystery about the elementary school and the court case that comes to dominate the final sections, a mystery that is never fully resolved.

The book covers a broad section of fields: spirituality, folklore, cultural insight, political apathy, legal deficiencies, social values and the role of gaman (endurance, fortitude). Of particular concern for this blog is the conclusion Parry comes to after his intensive examination of the tragic events.

When opinion polls put he question ‘How religious are you?’, Japanese rank among the most ungodly people in the world. It took a catastrophe for me to understand how misleading this self-assessment is. It is true that the organised religions, Buddhism and Shinto, have little influence on private or national life. But over the centuries both have been pressed into the service of the true faith of Japan: the cult of the ancestors.

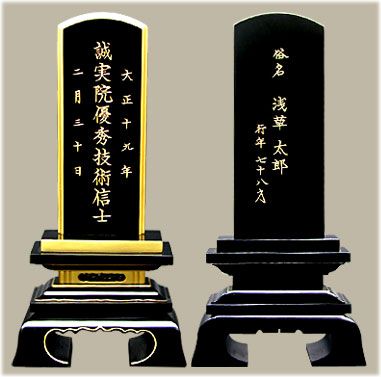

A typical butsudan, family altar for the dead

Parry follows this up with a description of the part that the family altar, the butsudan, plays in Japanese life. The dead are represented in the form of memorial tablets called ihai (black lacquered wood, on which is inscribed the posthumous name of the deceased). The contract between the living and the dead is simple: the dead will watch over the living as long as their memory is cultivated by respectful attention. Offerings of food, fruit and drink etc. are placed before the altar, a bell is rung to summon attention when paying respects, and reports made about important family developments. ‘The dead are not as dead there as they are in our own society,’ Parry quotes religious scholar, Herbert Ooms, ‘It has always made perfect sense in Japan as far back as history goes to treat the dead as more alive than we do … even to the extent that death becomes a variant, not a negation of life.’

The diligence with which Japanese tend to family graves is a further indication of the importance of the dead in the life of the living. And most of the kami that rule people’s lives are simply dead ancestors with special powers. Memorial days for the deceased are marked in religious fashion, and at the great festival of the dead in the summer, known as Obon, the sense of closeness to the dead reaches a peak as the veil between this world and the next opens and spirits return for the three days between the welcome back festivals and the sending off festivals.

The memorial tablets known as ihai that bear the posthumous names of the deceased

It’s possible to read Parry’s book as one long treatise on the role of the dead in Japanese society. ‘When grief is raw, the presence of the deceased is overwhelming,’ he writes. ‘When there’s a fire or earthquake, the ihai are the first thing that many people will save, before money or documents,’ a priest observes. ‘I think that many people died in the tsunami because they went home for the ihai. It’s life, the life of the ancestors.’

For the simple down-to-earth villagers of Tohoku, the tsunami was a cruel interruption to the normal pattern of their lives. Family altars, family graves and family ihai were swept away forever. And those who had died prematurely and were robbed of their dreams become gaki, or hungry ghosts, destined to wander the earth unhappily. Placating them is a vital matter, but impossible when even the necessities of life for survivors were missing. And what of the ancestors who had lost all their living descendants and had no one to care for them?

The book is notable for the way the survivors talk to the dead, comfort them, and show a strong sense of closeness. In such circumstances it was only natural that there should be a swarm of ghostly sightings, and the number of spirits roaming the landscape is striking – there are descriptions of possession, mediums who communicate with the dead, and in one remarkable case a Buddhist priest who exorcises no fewer than 25 different tsunami victims from a single woman.

At this point I couldn’t help thinking of that great ghost believer Lafcadio Hearn, and indeed he was the first foreigner to lay out in book form the central role of ancestor worship in Japan. Surprisingly Parry doesn’t reference him, even when talking of the kaidan, the strange tales, that characterised Tohoku folklore in the past and did so again after the tsunami. (In a note Parry acknowledges use of a more recent book on the subject, Robert J. Smith’s Ancestor Worship in Contemporary Japan, 1974.)

Graveyeard lanterns at Obon welcome the dead back to their descendants

What comes over strongest of all in Parry’s account is the relentless, almost obsessive drive of survivors to locate the bodies of their family kin. This goes on in some cases for weeks and months of unending toil, even in one case turning into a lifelong quest for closure. Sometimes it results in gory encounters with mud-sodden corpses, rotten beyond recognition, yet still there is a sense of relief, comfort even in having located the body. It’s as if the spirit is still attached and can’t be consoled until the physical entity is properly processed. The Japanese determination to repatriate the remains of soldiers who died in WW2 can be seen in similar light.

In plunging into the depth of misery caused by the disaster of March 11, Parry captures the essence of the Japanese soul. In the passing of the baton from one generation to the next, there’s something very consoling for the memory of the dead is fostered by the living, who in turn are watched over by the deceased. But when disaster strikes, it can all go tragically wrong. You couldn’t get a more vivid depiction of this most Japanese style of disaster. The book is simply a tour de force that exposes the true bedrock of the country’s religious thinking.

***************

For Lafcadio Hearn and ancestor worship, see here. For Hearn and ‘ghost-houses’, see here. For more on ancestor worship, see here. For another review of Parry’s book, click here. For other pieces related to ancestor worship, see the relevant Category in the righthand column.

Leave a Reply