This is Part Five of my journey the length of Japan, from the extreme north of Hokkaido to the southernmost train station in Honshu (Ibusuki). The material is extracted from a longer account to be published in due course. (For Part One of the journey, please click here.)

***************

Ainu Museum

Hirota san and I were headed for Shiraoi, our destination the newly opened Ainu National Museum. It was just an hour’s train ride from Sapporo and had won positive reviews, not just as a showcase for Ainu culture, but as the focus of a drive for revival. From the station the museum is a few minutes walk away, and the picturesque setting beside a wood-encircled lake certainly promised well.

Isabella Bird visited Shiraoi on her trip to Hokkaido in 1878. At the time the indigenous folk lived in separate settlements from the mainstream Japanese (called Wajin) , and she found her Ainu hosts to be unfailingly courteous and mild-mannered, with a lifestyle that was underwritten by a strong religious code. Her purpose was to see if they were good missionary material, but it seemed they had no need of Christianity for they were ‘more truthful, hospitable, honest, reverent and kind to the old than the lower class of Western cities’.

In the Museum’s spacious Exhibition Hall is an attractive display of patterned robes. These were painstakingly made in a process that began with the making of thread from inner bark fibre. The robes were embroidered, sometimes appliquéd, and the swirling patterns indicated the region from which they came. Like kimono, the robes became treasured heirlooms.

Around the room are panels explaining aspects of the culture. One section gave an overview of the history, suggesting the Ainu were a branch of the Jomon linked to ethnic groups in Sakhalin and north-east Siberia. For millennia Ezo (Hokkaido) was their home base, but the Meiji Restoration brought forced integration. Their land was appropriated, the language banned, religious practice forbidden, and customs such as tattooing forbidden. Meanwhile, compulsory education taught children Japanese language and culture. It is a familiar story of the way native people were treated by conquerors around the world.

Just as in the US, newly arrived settlers brought disease with them to which the Ainu had no immunity. It led to a drastic decrease in number, and as communities were broken up by forced relocation, many sought escape by intermarriage or passing off as mainstream Japanese. Ignored by Tokyo, the Ainu were discriminated against and not even officially recognised.

Only in 2008, after international pressure, did the government acknowledge ‘an indigenous people with a distinct language, religion and culture’. By this time a once vibrant culture had been reduced to scattered villages, and though numbers are disputed, it is thought that fewer than 30,000 now self-identify as Ainu. Many work in tourist shops where they put on ethnic clothing and carve wooden goods or make fabrics with traditional markings. Isabella Bird would be horrified. Writing 150 years ago, she claimed that the Ainu way of life was so well rooted that there was little danger of them dying out.

******************

In the museum grounds is a performance area where music, dance, and story-telling are staged. Like other aspects of the culture, the activities were an expression of Ainu spirituality, designed to enhance their relationship with the kamuy. The musical instruments featured a type of mouth harp called mukkuri and a guitar-like instrument called tonkori. These accompanied dances, one of which was an inclusive circle dance of such simplicity that old and young alike could take part – the audience too.

One feature I expected to see was a section on saké, or the Ainu version of it, for Isabella Bird was struck by the vital role it played. ‘The one thing they care about,’ she wrote. Rituals were initiated with libations involving the sprinkling of alcohol (as in Siberian shamanism), and imbibing was seen as a means of communing with the kamuy.

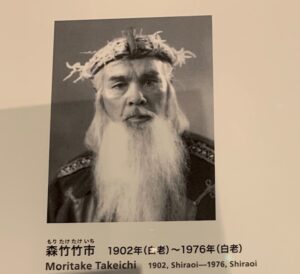

‘Break on through to the other side,’ sang Jim Morrison, and for Ainu saké was the means. Something of the intoxication of an Ainu gathering is captured in verse by Itakutono, who under his Japanese name of Moritake Takeichi wrote poetry about the sad decline of Ainu culture.

The Ainu Dance

From a big bowl full of homemade saké

The Ainu drink. Dance, dance!

Clapping to the fascinating rhythm

All through the autumn night,

Hoya– hoya!

Jangling earrings, sparkling necklace,

Glistening sword enliven the dance,

The gods are happy too. Dance, dance!

All through the autumn night,

Hoya– hoya!

Language is the very lifeblood of a culture, so the stark heading of a panel display spoke volumes – ’Linguisticide’. Ainu has the same structure as Japanese (subject – object – verb), but is otherwise grammatically different and belongs to a separate language group. Some linguists assign it to a group of its own with regional variations in Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands. The language has no script, but there was an opportunity to hear it spoken on the day I went when a recital was given of a traditional tale. In abridged form, it went something like this…

“Long ago there was a hunter of bears and deer, who felt the urge to go to the mountains, so he took his boat and paddled upstream, but it took longer than he expected, and foolishly he had taken no food. By the time he reached the mountain he was exhausted and hungry. It was growing dark and unpleasantly cold. He wondered if he would survive the night, but crows took pity on him, brought him meat and covered him over like a blanket. Next morning when he awoke, they were gone. Not a single one was to be seen.”

At this point the storyteller got up and left, though no one in the small audience seemed sure if it was just a dramatic pause Was it about connections, about being an integrated part of nature? Or did it imply that the crows were divine agents of a protective mountain-god? Whatever the subtext, it was easy to imagine it as the kind of mythic entertainment that once gripped the imagination of young children seated round a fire in an age when the world truly was magical.

At the lakeside were a few houses built in traditional manner, with an A-shaped wooden frame covered with thatched reed and woven bamboo grass. We were invited into one of the buildings, to find a single large room with high ceiling and open hearth. Here we were told about the bears with which Ainu are closely associated.

The bear cult is the most well-known part of Ainu culture, but it is also the most misunderstood. The idea that Ainu worship bears is so widespread that even Alan Booth repeated it, but it is not individual bears as such that they worshipped, but the Great Bear Spirit. There’s a big difference, as big as that between worshipping humans and worshipping a Great Human Spirit, named God.

For the Ainu, bears were the strongest and bravest of animals, with which they felt a kinship through sharing similar hunting patterns. Killing bears was a perilous and bloody business, and to ensure success the Ainu made offerings to the Great Bear Spirit for permission. The biggest festival of their year, called Iyomande (or Iomante), consisted of the ritual sacrifice of a bear cub which had been raised for a year or more by an Ainu ‘foster-family’ in a small cage. The ceremony involved firing arrows into the animal before skinning it and drinking its blood.

The slaughter was seen as a release for the spirit within the bear, which would attain immortality through joining with the Great Bear Spirit. In the acting out of resurrection through death, the rite thus enacted the cycle of winter decay and spring revival. Life must die so that life may live. Or as Joseph Campbell, the great mythologist, puts it, ‘You die to the flesh to be born in the spirit.’ (The practice of Iyomante has stopped now, but on youtube an anthropological video of 1931 shows the whole festival in detail, with much drinking, dancing and feasting.)

After our museum visit Hirota san and I happened on a soba shop, which was run by a middle-aged Ainu woman. There were a few patterned fabrics around the room, and a carving of an owl. ‘It is a lucky charm,’ she explained, ‘Owls were kamuy which protected the village.’ There were no other customers, and she told us of her childhood in Biratori-cho, a town with a sizeable Ainu community. She remembered being teased at school for being ‘a dirty Ainu’, and she could even remember attending the Iyomande ceremony as a child. ‘It was very cruel,’ she noted.

Her response to the museum was unexpected. ‘’Too late,’ she said dismissively. ’It’s not for Ainu,’ she said, it’s for Japanese. To make them feel better.’

‘But surely it’s good to show the culture and explain what happened?’ I objected.

‘What for? From Meiji time we were destroyed. And now there is no meaning.’

‘But isn’t it good to show the Ainu viewpoint?’

‘It is just a showpiece. It’s for Japanese so they feel better about things. Even the people working there are mostly Japanese. We don’t need a museum. They should give us back our land and our rights to fish and hunt.’

Just the day before I had seen an article in the Hokkaido Shimbun about the demand of an Ainu group to catch salmon in rivers, which is currently illegal. As the first such lawsuit to claim back indigenous rights, it was a landmark case, yet it was tucked away on an inside page.

‘So you don’t feel there’s any kind of revival?,’ I continued.

‘Revival of what? There is nothing to revive. I’m Ainu but what do I have? I don’t speak Ainu, no one speaks any more. My grandfather had a long beard and my mother painted her face. They practised old customs, but in secret. They didn’t want anyone to know. But my parents were not interested. They thought it better not to know. They wanted to protect me. There was a lot of discrimination in those days. There still is..’

Leave a Reply